Soap once ruled household cleaning until a class of surfactants known as alkylbenzene sulfonates emerged in the 20th century. Long before eco-labels and ingredient transparency, chemists wanted something that performed better in hard water and kept fabrics looking bright. The shift to linear alkylbenzene sulfonates, with sodium dodecyl benzene sulfonate (SDBS) as a flagship, came about when environmental and performance concerns collided. Early branched forms built up in waterways, causing public pushback and leading to legislative changes, mainly in Europe and North America. Today’s SDBS showcases decades of incremental tweaks in production, reflecting how society, chemistry, and environmental thinking cross paths.

SDBS belongs to the family of anionic surfactants. It’s usually found as a white or off-white powder or free-flowing granule, sometimes as a viscous liquid depending on how much water or salt is present. You’ll find it on ingredient panels for laundry detergents, household cleaners, and industrial degreasers. It’s cheap to make, works relentlessly in soft or hard water, and generates a healthy lather – the kind of consumer feedback that companies prize. Most folks don’t recognize its name, but nearly every busy kitchen and laundry room owes some of its clean surfaces to SDBS.

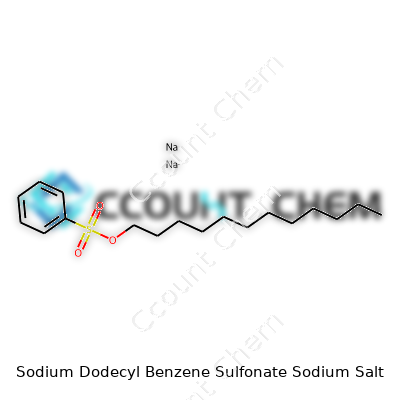

SDBS stands out for its powerful foaming and emulsifying ability. Its molecular structure includes a long hydrophobic dodecyl chain attached to a benzene ring, with a sulfonate group at one end. This balance of water-loving and oil-loving segments gives SDBS its punch when lifting greasy grime. The sodium salt form dissolves well in water, resists clumping in humid storage conditions, and doesn’t break down as easily as some earlier cleaners did in mineral-rich tap water. Its melting range and thermal stability match industrial expectations for large-scale cleaning operations.

A bag of SDBS carries a purity level, usually over 85%, and includes limits for inorganic salts and moisture. Most manufacturers flag a typical pH between 7.5 and 10 for a dilute solution. Particle size matters for how smoothly the material feeds into mixing systems and how rapid it dissolves during use. Labeling regulations call for hazard statements and safe handling tips. In the EU and US, ingredient lists must show standardized names so buyers or regulators can verify what’s actually inside. Compliance with REACH or TSCA builds trust — not only between companies and regulators, but also for end users who’ve grown wary of generic "cleaning agents" on labels.

Commercial SDBS gets produced through sulfonation. Linear dodecylbenzene reacts with sulfur trioxide or oleum, followed by neutralization with sodium hydroxide. These reactions take place in specialized reactors equipped with heat and emission controls, designed to keep workers and the environment safer. Production lines monitor acidity, reaction time, and temperature to enhance sulfonation efficiency and minimize by-product formation. Waste is treated to capture surplus acids and unused precursors, echoing ever-stricter laws for chemical manufacturing.

SDBS handles a range of conditions, staying stable in both hot and cold water. It breaks down slowly under typical sunlight and moisture exposure, so it persists in washing cycles unless specific degraders get involved. Chemists regularly tweak its chain length or substitute groups on the benzene ring to tune foaming or compatibility with enzymatic ingredients and fragrances. In some cases, SDBS forms the backbone for more specialized surfactants through further sulfonation or branching, giving rise to blends for tougher jobs in industry or personal care.

Shoppers and manufacturers dance around a surplus of names for SDBS, including sodium dodecylbenzenesulfonate, LAS (linear alkylbenzene sulfonate), sulfonic acid sodium salt, and the INCI name Alkylbenzene Sulfonate Sodium Salt. Older packaging, especially from certain parts of Asia, sometimes uses abbreviations or house brands that might confuse importers, but the underlying chemistry remains consistent. Each synonym points back to the same functional, high-foaming surfactant prized by detergent makers.

Working with SDBS calls for a combination of gloves, goggles, and good ventilation. At higher concentrations, SDBS can irritate skin and eyes. Mishandling dust or vapor during manufacturing leads to exposure risks, so companies install dust control and run regular air quality checks. In my own years on the production floor, training was never a one-off affair; supervisors repeated spill drills and safe transfer techniques. Workers read safety data sheets and rehearse how to use emergency eyewash stations, especially after a few stories of warehouse missteps or careless mixing. Environmental standards require proper wastewater treatment and storage systems to keep aquatic organisms from harm.

SDBS stars in detergents for laundry, dishwashing, hard surface cleaning, and industrial degreasing. Its lather appeals to consumers who want proof of cleaning action, especially in the age of “visible clean.” In industrial settings, SDBS breaks down oily deposits and residue on machine parts, scaling up to vats that process hundreds of liters at a time. Municipal water treatment plants sometimes use SDBS blends to keep filters and tanks clear, though recent attention to environmental impact urges operators toward lower-dosage treatments. Agricultural pesticide formulations rely on SDBS as a wetting aid to help droplets stick to plant leaves, ensuring chemicals aren’t wasted.

In research, SDBS functions as a starting point for exploring how molecular tweaks change surfactant behavior — foaming, degreasing, or toxicity. Universities and private labs have tested its interaction with hard water ions, temperature swings, and biodegradation rates. The push to replace petroleum-based inputs with renewable feedstocks has led to pilot projects trying fatty alcohols from palm or coconut oil instead of traditional n-paraffins, though questions about price stability and deforestation keep those projects under review. Having spent years reading R&D case studies, I see much of the effort focused on tailoring SDBS derivatives for specialty roles in oilfield recovery, emulsion polymerization, or rapid-release pharmaceutical coatings.

Multiple studies find SDBS causes mild to moderate skin and eye irritation, especially in concentrated form, with accidental ingestion leading to gastrointestinal discomfort. Regulators keep an eye on aquatic toxicity, since the compound lingers in water and can affect fish and algae after repeated exposure. Modern SDBS products have gotten less toxic over the decades, with improved formulas designed to break down faster — thanks to environmental monitoring and new regulations. Risk assessments push manufacturing plants to tighten discharge rules, and researchers keep looking for additives or enzymes that speed up breakdown after the product goes down household drains.

SDBS won’t disappear from the market any time soon, but companies and regulators both recognize that future growth requires cleaner chemistry and new approaches to sustainability. Makers keep scanning for ways to cut waste, upcycle by-products, or swap out fossil sources for plant-based starting materials. Hospitals and sensitive workplaces keep seeking less irritating alternatives, especially for repeated daily cleaning. In my own conversations with formulation chemists, there’s a sense that demand for “greener” surfactants is rising, putting pressure on SDBS plants to innovate around the core molecule. Progress comes slow, but industry habits shift once cost, performance, and eco-ratings align on a new path forward.

Most people never stop to wonder about the chemicals responsible for the bubbles in their dish soap or the foam in their laundry detergent. Sitting behind the scenes, sodium dodecyl benzene sulfonate sodium salt shows up in more places than folks realize. It stands out as a common ingredient in everything from cleaning sprays to car wash soaps. The reason is simple: it lifts dirt and grease like few other substances can.

Growing up, family chores always meant scrubbing dishes or mopping floors. I remember my hands covered in suds that cut through sticky food and oily residue. This hard-working surfactant helps water grip grime and lift it away. It breaks down oily messes, making them easier to rinse off. Factories all over the world use it in the production of liquid and powder cleaners. That foam that forms so quickly―that’s the surfactant in action. There’s science behind those bubbles, not just marketing.

Dirty clothes often smell because fibers hold onto oils. Once the washer fills, water alone barely nudges out stubborn grease. Sodium dodecyl benzene sulfonate, often shortened to SDBS for convenience, loosens those oily spots so they don't cling to t-shirts and sheets. Removing those stains means fabrics look newer and last longer. Reliable performance in both hard and soft water gives it a leg up, whether you’re running city tap or well water.

Factories trust this surfactant for more than just cleaning. Construction companies rely on it for concrete plasticizers, helping cement spread evenly and fill forms without leaving gaps. Textile mills use it during dyeing and finishing, since fibers need help soaking up colors. Farmers count on it, too. Sprayers need the solution to cling to plant leaves instead of rolling off. SDBS lets agricultural chemicals stick where they should, so crops get protected from pests or weeds more effectively.

Not everything with SDBS is positive. Prolonged exposure dries out skin. Years of washing dishes with bare hands have taught me how it can leave skin cracked and uncomfortable, especially during winter. The Environmental Protection Agency tracks surfactants because wastewater treatment plants only break down some types. If too much enters streams, aquatic life can suffer. Community efforts to upgrade water treatment stem from concerns about compounds like these. Reducing runoff helps, but consumers and companies still have to pay attention to what goes down the drain.

As a parent, I try to buy products friendlier to people and the planet. Smaller soap companies now experiment with biodegradable surfactants and packaging that cuts plastic waste. Ingredient transparency matters—families deserve to know what’s in their cleaners. Industry, too, can improve by designing surfactants that do just as much cleaning but break down faster in water. The push for greener chemistry keeps getting louder.

Sodium dodecyl benzene sulfonate isn’t vanishing anytime soon. As long as folks want spotless homes and clean clothes, it will play a big role. Responsible use and smart innovation will shape how we rely on it in the years ahead.

Sodium dodecyl benzene sulfonate—sometimes seen on product labels as SDBS—shows up in a lot of cleaning supplies at home. It’s a key reason why dish soaps and laundry detergents check all the boxes for cutting grease and lifting dirt. I’ve noticed it listed under some mysterious-sounding ingredient panels on dish soap or all-purpose spray. Manufacturers choose it for one big reason: it works. This surfactant breaks up oily messes fast and leaves things looking clean. That’s the clear upside.

Researchers have spent plenty of time checking SDBS for problems in home settings. The FDA keeps an eye on it for food-related uses and sets limits, while the EPA and European regulators track its impact on people and the water supply. SDBS stands out because it’s not likely to build up inside your body. Skin contact is the main route for most folks at home, since it doesn’t turn into fumes you inhale, and you’re not swallowing your dish soap (at least I hope not). Health scientists point out that, for most people, SDBS rinses off the skin quickly with water and doesn’t hang around. No evidence links it to cancer or hormone problems in the amounts people find at home.

Problems appear only in certain cases. If you use the product straight from the bottle without gloves or suffer from skin conditions like eczema, irritation or dryness can occur—especially if you use it every day. Eye stinging pops up if you splash it by accident, but the irritation fades with a good rinse. Serious allergic reactions rarely happen.

I’ve watched warnings about what cleaning agents do to fish and rivers. SDBS does break down faster than some older chemicals, though not instantly. Wastewater plants can lower most of its environmental punch, but some amounts reach rivers and lakes. Fish and tiny water organisms feel it at high concentrations—nowhere near what most homes send down the drain, but enough that regulators set strict rules for factory dumping or big spills. Regular household use doesn’t drive these levels, though collective runoff from millions of sinks matters.

The best advice for families: store cleaning sprays and soaps out of reach of kids. If SDBS gets on skin or in eyes, rinse well—soap isn’t supposed to linger on you anyway. Gloves help if you notice your hands getting dry, especially in winter. Stick to the label instructions for diluting and using products, since stronger isn’t always better for dirt or your skin.

It’s always a smart move to look at greener cleaning choices when possible. Companies have started offering cleaners powered by other surfactants from plants or minerals. These alternatives sometimes skip harshness altogether, though they may cost more or feel different. SDBS is safe for day-to-day cleaning if you use it with some common sense. Everyone deserves a clean home that doesn’t cost your health—or the environment—down the line.

Sodium dodecyl benzene sulfonate sodium salt finds its way into all sorts of products. You find it in laundry detergents, dishwashing liquids, and even cleaners used every day in homes and workplaces. The structure of this compound explains why it handles grease and grime so well, and it also raises questions about how we balance cleaning power with safety for health and the environment.

This molecule has two key parts. One end contains a long carbon chain, made up of twelve carbon atoms linked in a row—this is the "dodecyl" part. Chemists call this section hydrophobic, which really just means it doesn’t play nicely with water but loves to grab onto oily messes. Connected to the other end is a benzene ring, a classic six-carbon cycle known for its stability and wide use in chemistry. Stuck to this ring is a sulfonate group (-SO3-), which bonds with sodium ions to create the sodium salt form. This part loves water (hydrophilic), so it helps the molecule dissolve well and mix in with liquids.

This simple layout—a greasy tail and a water-loving head—means sodium dodecyl benzene sulfonate acts as a surfactant. From my years cleaning up after projects and spills, I can vouch for the way surfactants break up stubborn stains. One end sticks to grease, the other pulls that grease into water so you can wash it away. No single molecule does all the work alone, but together they form tiny spheres called micelles—these grab oils or dirt so they don’t land back on clothes or dishes. Plenty of research backs up just how well this action removes stains and boosts cleaning results.

Scientists have mapped this structure down to the atom. The backbone of sodium dodecyl benzene sulfonate follows a chain of carbon atoms, hits a benzene ring, then ends with a sulfonate group. Its molecular formula sums up as C18H29NaO3S. This combination gives it a unique way of working that sets it apart from simpler soaps, especially when dealing with hard water and tricky soils. Data from cleaning trials and industry assessments shows it stands up to both dirt and mineral content, not just in the lab but also in daily life.

Any structure built to break up grease so easily brings tradeoffs. Scientists have pushed for safer, more biodegradable surfactants after learning that long-lasting molecules can harm rivers, wildlife, and water supplies. My time looking into wastewater cleanup shows that even good cleaners can cause harm if not properly handled. The benzene ring and sulfonate group mean this surfactant isn’t as quick to break down in the environment as some alternatives, so regulators and companies look for ways to treat or replace it as much as possible. Green chemistry efforts focus on tweaking the molecule so it still works but leaves less residue behind.

Many companies now study every ingredient, comparing cleaning strength, cost, and how quickly each compound breaks down after use. Clear labeling, more research into alternative surfactants, and better treatment of industrial waste will help. Anyone grabbing a cleaning bottle benefits from knowing what’s inside, and even small choices—like using the right amount—can help lower environmental impact. As more people understand the science behind cleaning products, smarter use and better design become more likely, shaping the future of everyday chemistry in our homes.

Anyone who has glanced at the label of a cleaning product or shampoo has run across long chemical names that don’t always inspire trust. Sodium dodecyl benzene sulfonate sodium salt, often shortened to SDBS, stands out as one of those names. It shows up in all sorts of products that need to get rid of dirt and oil, especially in laundry detergents and industrial cleaners. The ingredient acts as a surfactant, which means it helps water mix with oil and grease, so they wash away more easily. The real question: Should this ingredient show up in personal care items like facial cleansers and shampoos?

Many cosmetic manufacturers look for ingredients that provide efficient cleansing at a low cost. SDBS does the heavy lifting in industrial cleaning. The texture it creates can make products lather richly, which some folks like because foamy bubbles feel like they’re working harder. Yet, I’ve learned from years of reading the ingredient lists on everything from dish soap to face wash, not everything that cleans well is kind to the skin.

This surfactant strips away oils rapidly. That might sound great until you think about the skin’s natural barrier. Our skin relies on a thin film of natural oils and moisture to stay resilient. Aggressive surfactants can undermine that barrier, leading to dryness, irritation, and—if you have sensitive skin—red patches and itchiness.

SDBS can cause irritation on direct contact with the eyes or skin, especially in higher concentrations. The Journal of the American College of Toxicology has shown that SDBS, in more concentrated forms, often causes irritation and has uncertain effects on long-term skin health. This is the reason behind strict limits on how much can appear in leave-on products. In rinse-off products, exposure time is short, but those with allergies or skin conditions can still have reactions.

The cosmetics industry has rules, but some loopholes allow lesser-known chemicals like SDBS to slip into products. The U.S. FDA does not approve every cosmetic ingredient before it hits the shelves, so companies carry the responsibility to ensure safety. The Cosmetic Ingredient Review Expert Panel—a group that studies ingredient safety—notes that SDBS can be used safely in rinse-off products up to a certain percentage. Europe takes a tougher stance; the European Chemicals Agency has categorized it as hazardous for eye and skin irritation, enforcing stricter labeling and usage controls.

People who want to play it safe should steer clear of strong detergents in personal care items. I’ve learned through trial and error that labels like “gentle,” “sulfate-free,” or “for sensitive skin” usually mean the company uses milder surfactants—ingredients less harsh on skin, like sodium cocoyl isethionate or decyl glucoside. Even something as basic as checking for fewer mystery names can make a difference for skin comfort and peace of mind.

Plenty of alternatives exist that clean well but treat skin with more respect. The move toward transparent ingredient lists and gentler formulas covers more than just a trend—it reflects what people want after years of rough scrub-downs. Companies exploring plant-based surfactants or milder synthetic cleansers respond to this shift. Clear, honest communication paired with thoughtful formulation could prevent the harsh sting or dry feeling SDBS sometimes leaves behind. More consumers need to look out for what feels best for their own skin, rather than what promises the most foam or biggest bubbles.

Sodium dodecyl benzene sulfonate sodium salt has a long name and a strong reputation in cleaning and detergent products. It’s effective at breaking up grime, but it’s not exactly gentle on the body or the environment. Even low exposure can irritate skin and eyes. I’ve seen colleagues come away with burns after working with surfactants like this one, so taking its handling seriously is not just about ticking compliance boxes. These are chemicals that shape everyday cleaning, yet mishandled they also put people in harm’s way.

This isn’t the kind of powder or liquid you tuck away anywhere. Air, moisture, and direct sunlight chip away at product stability. A dry, cool room, away from any heat sources, prevents the powder from clumping and the liquid from breaking down. Good airflow keeps fumes from pooling. Some may think tossing chemicals under a workbench is fine, but that leads to spills, ruined materials, and uncomfortable phone calls with your safety officer.

Using chemical-resistant shelving, like high-density polyethylene or powder-coated metal, protects against accidental leaks. Labeling helps, too, for quick identification in a pinch. From my experience, storing this compound above eye-level spells trouble. Keep it low, limit the risk of dropping heavy containers, and save your back and eyes.

No one should scoop, pour, or transfer this chemical with bare hands. Gloves—nitrile works well—stand between your skin and irritation or worse. Protective glasses or a face shield stop splashes from reaching your eyes. The stinging pain of a chemical in the eye isn’t something anyone forgets, and safety data sheets spell out the risk.

Wearing a dust mask or using extraction fans makes breathing easier in dusty areas. I’ve worked jobs that insisted on wearing full respirators; it’s hard to complain once you’ve felt a sore throat after inhaling fine chemical dust.

Accidental spills happen, but panicking or ignoring them makes a small problem huge fast. Absorbent materials clean up liquids, and you never mix sodium dodecyl benzene sulfonate sodium salt with other chemicals in the sink. Once I made the mistake of thinking ordinary soap worked for every kind of cleanup—it didn’t, the spill took longer to fix, and the area stayed off-limits for hours.

Always put waste in a labeled, sealed container. Don’t toss leftover powder or used gloves with household garbage. Disposal rules differ by city. Some places treat even low-hazard materials as hazardous waste, and it’s not just red tape. Contaminated water sources create real environmental headaches. Following local regulations, maybe checking with environmental authorities, means you do your bit to protect neighbors downstream.

People working with chemicals need training, not just a printed sheet of instructions. Regular reminders actually keep safety fresh in people’s minds. I’ve learned that stopping for a quick talk on safe handling prevents accidents better than after-the-fact warnings. Buddy systems, safety drills, and clear signage all build a safer workspace.

Handling chemicals like sodium dodecyl benzene sulfonate sodium salt isn’t rocket science, but it takes steady attention and a bit of pride in doing things right. You look after yourself, your crew, and the environment, one step at a time.

| Names | |

| Preferred IUPAC name | sodium 4-dodecylbenzenesulfonate |

| Other names |

Sodium dodecylbenzenesulfonate SDBS Linear alkylbenzene sulfonate sodium salt Laurylbenzenesulfonic acid sodium salt Dodecylbenzenesulfonic acid sodium salt |

| Pronunciation | /ˈsoʊdiəm doʊˈdiːsɪl bɛnˈziːn sʌlˈfəneɪt ˈsoʊdiəm sɔːlt/ |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | 25155-30-0 |

| Beilstein Reference | 1309372 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:34755 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL1742702 |

| ChemSpider | 22413 |

| DrugBank | DB11105 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 03c55291-b3da-4bb1-9703-1b3e907c2a4e |

| EC Number | EC 246-680-4 |

| Gmelin Reference | 81630 |

| KEGG | C16525 |

| MeSH | Dodecylbenzenesulfonates |

| PubChem CID | 23614 |

| RTECS number | DB6600000 |

| UNII | W63P5V51AB |

| UN number | UN3077 |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | DTXSID4020663 |

| Properties | |

| Chemical formula | C18H29NaO3S |

| Molar mass | 348.48 g/mol |

| Appearance | White to light yellowish powder |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | 0.35 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | Soluble in water |

| log P | -2.7 |

| Vapor pressure | Negligible |

| Acidity (pKa) | -6.5 |

| Basicity (pKb) | 12.7 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | -22.5×10⁻⁶ cm³/mol |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.485 |

| Viscosity | 50 cP (20°C) |

| Dipole moment | 6.6 D |

| Thermochemistry | |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 365.6 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -554.42 kJ/mol |

| Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) | -7967 kJ/mol |

| Pharmacology | |

| ATC code | D08AJ01 |

| Hazards | |

| Main hazards | Causes skin and eye irritation. Harmful if swallowed. May cause respiratory irritation. |

| GHS labelling | GHS02, GHS05, GHS07 |

| Pictograms | GHS05,GHS07 |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | H315, H318, H412 |

| Precautionary statements | P264, P280, P301+P312, P302+P352, P305+P351+P338, P330, P337+P313, P332+P313, P362, P501 |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | 3-1-0-ALC |

| Flash point | > 180°C |

| Autoignition temperature | > 350°C |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 oral rat 438 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | 438 mg/kg (rat, oral) |

| NIOSH | SN3225000 |

| PEL (Permissible) | PEL: Not established |

| REL (Recommended) | REL (Recommended): 3 mg/m³ |

| IDLH (Immediate danger) | Not listed |

| Related compounds | |

| Related compounds |

Dodecylbenzenesulfonic acid Linear alkylbenzene sulfonate Sodium lauryl sulfate Sodium xylene sulfonate Ammonium dodecylbenzenesulfonate |