Decades ago, researchers set out to solve problems involving buffering in biochemical experiments. The usual suspects, like phosphate or acetate buffers, struggled to maintain pH under certain conditions. Sodium 3-morpholin-4-ylpropane-1-sulfonate, known in many labs as MOPS-Na, came out of that search. Invented during a period of chemical optimism in the 1960s and 1970s, MOPS-Na grew in popularity with the expansion of protein and nucleic acid research. Scientists looking for stability and minimal interference in their results steadily adopted it. Journals from the late 20th century show an uptick in protocols mentioning “Good’s buffers,” a family where MOPS belongs.

Sodium 3-morpholin-4-ylpropane-1-sulfonate, often shortened to MOPS sodium salt or MOPS-Na, carries a straightforward mission—help researchers maintain pH balance in their experiments. Laboratories interested in maintaining specific buffer conditions depend on this compound for its low reactivity and clarity in aqueous solutions. Manufacturers aim for material with low heavy metal content and minimal organic contaminants, knowing molecular-level impurities can cloud experimental outcomes.

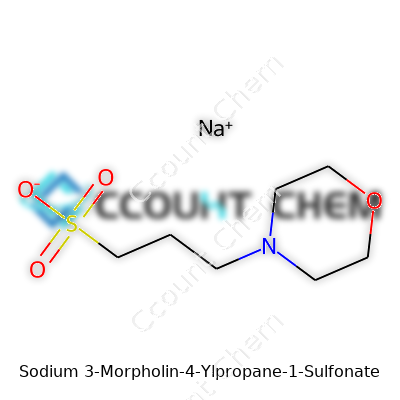

MOPS-Na appears as a white, crystalline powder, dissolving quickly in water to produce a clear, colorless solution. Its molecular formula is C7H15NNaO4S, and it sits at 229.25 g/mol molecular weight. It boasts a pKa near 7.2 at 25°C, making it an ideal buffer for work around physiological pH. The compound demonstrates solid solubility, resisting precipitation and breakdown under normal lab conditions. Stability under autoclaving and a lack of interaction with divalent cations bump it up on many wish lists for biological research.

Product labels for MOPS-Na highlight several parameters: purity measured by titration (often above 99%), chloride, sulfate, and heavy metal traces, water-insoluble fraction, and pH of a standardized solution. Reputable companies add lot numbers for traceability, making recall or root-cause analysis feasible if problems occur. Labels show storage conditions—sealed containers, temperature ranges (commonly room temperature or cooler), and warnings for moisture ingress, as clumping degrades performance.

Most MOPS-Na in laboratories and industry gets synthesized by reacting morpholine with propane sulfonic acid derivatives under controlled conditions, followed by neutralization with sodium hydroxide. Manufacturers keep a close watch on temperature and pH throughout the synthesis, since off-specification intermediates can create side products. Filtration and recrystallization finish the process, stripping out unreacted materials and concentrating only the buffer-forming salt. Each producer relies on slightly different purification techniques, depending on their equipment and purity goals.

In routine use, MOPS-Na actively resists chemical breakdown. It doesn’t undergo significant side reactions with most biochemical reagents. When exposed to strong oxidizers or acids, some decomposition may occur, but in the context of routine buffer capacity and protein work, stability rules. Attaching markers or linking groups for specialized applications rarely messes with the buffering core. Scientists have experimented with modified morpholine rings or altered sulfonate positions, but the original structure remains the go-to for most buffer applications because of its reliable performance in enzyme tests, protein purification, and cell culture.

Researchers or suppliers might call MOPS-Na by several other names, including 3-(N-Morpholino)propanesulfonic acid sodium salt, or use brand names like MOPS Sodium Salt Buffer or Sodium MOPS. Some catalogues list the CAS number 113295-35-7, which helps labs find the proper material. Awareness of these alternate labels saves time and money, as confusion with similar sounding buffers—like MES or HEPES—leads to failed experiments and repeat orders.

Lab work with MOPS-Na rarely introduces major hazards. Splashing the powder or solution into eyes can cause irritation, so lab goggles and gloves stay on the checklist. Laboratories keep MSDS sheets on hand that note that inhalation or accidental ingestion may cause mild symptoms. Most authorities place MOPS-Na in the lowest risk categories, but following good housekeeping and immediate clean-up routines prevents issues. Experimenters know that contamination or uneven pH can ruin days of sample prep, so storage in dry, closed containers matters for both personal safety and data integrity.

MOPS-Na shows up in a wide circle of laboratories and industrial plants. Molecular biology, biochemistry, clinical diagnostic kit production, protein purification, and cell culture all call for stable pH environments that don’t sabotage sensitive reactions. Geneticists running electrophoresis or protein separation depend on its buffering action, especially when working with RNA, since MOPS-Na avoids unwanted side reactions or signal interference. In vaccine development or research with recombinant proteins, downstream purification steps rely on MOPS-Na’s gentle touch and consistent performance. Manufacturing semiconductors or specialty coatings sometimes needs pH control at fine scales, prompting engineers to turn to high-purity buffer salts like this one.

Innovation around buffer technology never slows down, since the march toward higher accuracy, gentler processing, and lower cost continues. R&D teams examine how MOPS-Na handles new classes of enzymes, emerging biologics, and large-scale automated processes. Customization for high-throughput platforms, tiny reaction chambers, or combined buffer and stabilizer blends sparks ongoing collaboration between chemists and biologists. Development of alternative forms, such as pre-measured tablets or liquid concentrates, aims to reduce handling time or human error in multi-well assays.

Extensive studies show MOPS-Na behaves safely in typical lab settings, with low acute toxicity to humans and minimal environmental impact under planned disposal routes. In animal models, it does not trigger significant adverse effects at concentrations used in biochemical research. Inhalation or direct skin exposure causes only mild and temporary irritation, so facility risk assessments rarely flag it for unusual controls. Regulatory authorities still call for standard protective practices, but years of published safety data reassure both new students and seasoned experimenters.

Demand grows for higher quality buffers as synthetic biology, gene editing, and cell therapy fields expand. Producers prepare for larger production runs, tighter impurity profiles, and quicker supply chain response as research becomes more global and time-sensitive. Advances in automation and environmental monitoring tools seek even greater purity and transparency, aligning buffer production closer with pharmaceutical standards. As pressure rises to minimize environmental impact, recycling and green chemistry options for buffer production and disposal gain traction. MOPS-Na, with its strong track record and adaptability, seems set to remain a fixture, but new derivatives and application methods could reshape what laboratories expect from their cornerstone pH stabilizers.

Sodium 3-morpholin-4-ylpropane-1-sulfonate shows up in labs everywhere, often under the nickname MOPS. People who have spent time around biochemistry benches or molecular biology work know this white powder well. Its real claim to fame comes from its steady work as a biological buffer. Almost every time I’ve prepped an RNA gel or run a sample through electrophoresis, MOPS has made sure the pH didn’t swing wild and ruin the result. Without such buffers, labs would deal with inconsistent results, wasted effort, and a lot of head-scratching over failed experiments.

Keeping pH steady isn’t just a technical detail. Research into proteins, nucleic acids, and enzymes often depends on strict pH ranges. A small slip turns a biological reaction weird and unpredictable. MOPS holds its pH right around 7.0, which sits in that comfortable, neutral spot where most living processes take place. Because it doesn’t get in the way of many chemical or enzymatic reactions, researchers have leaned on it for decades.

I remember the frustration of using buffers that let pH drift or, worse, reacted with the chemicals we were trying to study. That extra layer of reliability makes the day smoother and the data stronger. MOPS delivers again and again on that front.

Electrophoresis might sound fancy, but anyone who’s worked with it will tell you it can get fussy. Gels need stability to separate RNA or DNA strands based on size. MOPS buffer keeps things calm, even as high voltages run through the gel box. If the pH strays, you end up with warped bands, degraded samples, or smeared results no one can trust.

In the early days of molecular biology, researchers used different buffers for each experiment, learning by trial and error. MOPS stood out because it covers the right biological range and doesn’t interact with a lot of the side chemicals used in common protocols. Its chemical structure brings strength: the morpholine ring and sulfonate group help it keep charge and function stable despite electrical currents or temperature changes.

Every chemical brings challenges. People rarely think about what goes down the drain after the experiment ends. Sodium 3-morpholin-4-ylpropane-1-sulfonate doesn’t break down overnight in nature. That sends a message: labs need better waste policies, not just for MOPS, but for all “everyday” chemicals.

Training undergraduates in proper buffer disposal takes effort. It’s tempting to treat lab buffers as harmless, especially compared to the harsher stuff stored under lock and key. Establishing clear procedures for neutralizing and collecting buffer waste isn’t about paperwork—it's about long-term health for everyone downstream. Setting up in-house protocols for waste treatment or working with suppliers on greener alternatives matters just as much as pipetting the right amount the first time.

Sodium 3-morpholin-4-ylpropane-1-sulfonate will keep holding the fort in labs all over the world. It won’t make headlines, but real progress in research relies on these behind-the-scenes workhorses. As the scientific community takes sustainability more seriously, even mainstay reagents like MOPS deserve a second look—not just for lab performance, but for how we handle them from start to finish.

A product label might print a few words: “Store in a cool, dry place.” To many people, this feels obvious. Tossing an item into a cabinet or the pantry seems like enough. In reality, mistakes happen not because of complicated science, but because someone doesn’t pay attention—or doesn’t know how much can go wrong when a product sits in the wrong spot for weeks or months.

My time working in the food business taught me more about storage than any instruction manual ever could. Wheat flour, for example, pulls moisture from the air if the container doesn’t close tight. Not only does it spoil quicker, but it can also attract pests. No one wants to open a sack and find little bugs crawling around.

Medicine comes with even stricter guidelines. It’s easy to believe a bottle of pills can handle anything, but heat breaks down some drugs. High humidity causes others to clump or lose effectiveness. One summer, a shipment of antibiotics sat in a storage room with an air conditioner on the fritz. Weeks later, we found the pills had changed color, signaling breakdown. The cost to restock that batch cut into already slim margins and delayed treatments for patients.

Science backs up what experience shows. The World Health Organization recommends storing most medicines between 15°C and 25°C (59°F to 77°F). Some products—vaccines, probiotics, even certain cosmetics—must stay colder, often between 2°C and 8°C. A simple swing above that, even overnight, can ruin an entire supply. A study from 2022 reported that up to 10% of vaccines in developing regions lost potency due to improper storage, erasing months of hard work for healthcare teams.

Food safety agencies keep rules simple: keep dry products away from moisture and perishable items cold. Even small changes add up. A potato in a cool, dark drawer will last for weeks. Leave it on the counter in the sunlight and, before long, green spots show up—along with toxins unsafe to eat.

Most problems don’t require expensive tech. Airtight containers, coolers, dry shelves off the ground—these simple tools keep out humidity, bugs, and temperature swings. Check dates and rotate stock so older products leave first. Employees should know what to watch for: funny smells, discolored packaging, sticky residue.

Training matters as much as the right hardware. I’ve seen the best climate-controlled warehouse go to waste because no one reported a dripping pipe. If no one feels responsible for watching storage, mistakes slip through. Regular check-ins help. Even home pantry storage benefits from a quick glance every week.

Keeping products under the right conditions saves money and protects health. Spoiled goods lead to more than just financial loss—they put families and communities at risk. Setting up proper storage isn’t only for the big players in healthcare or food. It applies in any home or small business. Trust experience, trust research, and keep a close eye on temperature, humidity, and cleanliness. These are the details that make the difference.

Anyone working in a lab or factory will agree: new names in the chemical world can cause a pause. Terms like Sodium 3-Morpholin-4-Ylpropane-1-Sulfonate don’t roll off the tongue. Working around chemicals with names like that gets people thinking about risks, especially if they’re handling them daily. Lab legends stick—someone always tells a story about red hands or a bad reaction. Understanding what’s actually in a solution helps clear away some of that fog.

Sodium 3-Morpholin-4-Ylpropane-1-Sulfonate shows up on ingredient lists for buffer solutions and some biochemistry protocols. Researchers use it for its ability to keep pH steady in all sorts of experiments. Ask any bench scientist, and they’ll say most common buffer agents have been tested for basic risks. Direct data, though, remains surprisingly scant for some specialty chemicals. This one lands in that category.

Dig into safety databases—like the European Chemicals Agency or U.S. National Library of Medicine—and clear long-term studies on this substance rarely turn up. The lack of headlines means no massive accidents, but it also leaves gaps. Most documents suggest it isn’t considered acutely toxic if it touches skin or gets swallowed in tiny experimental amounts. The compound does not pop up in lists of major irritants or carcinogens. Still, stories from technicians teach you that low hazard does not equal no hazard. Tiny exposures day after day hold their own risks.

Protective measures stand out as the real lesson from years handling chemicals. Gloves matter even when labels show low concern. Sodium sulfonates like this one don’t usually penetrate skin fast, but eyes react quickly to fine powders and dust. People in my circle who have handled similar sulfonate salts talk about stinging sensations when dust floats in the air. Even without red flags in big studies, that firsthand sting speaks volumes.

Ingestion almost never happens on purpose in a lab. Swallowing chemicals can quickly turn into nasty surprises with symptoms that don’t always match the hazard label. While official records suggest low acute oral toxicity for this compound, that hinges on using tiny test animals—not humans, not day-to-day life, and not years of exposure.

Watching wastewater collection in industrial settings makes another risk jump out: environmental buildup over time. Sulfonate salts wash away with water, and though they do not belong on major lists of persistent or bioaccumulative compounds, there’s no guarantee for long-term impact. Responsible companies don’t dump used buffers down the drain but collect them for disposal instead.

Clear labeling, ongoing safety training, and good habits protect more people than any legal threshold alone. Wearing gloves draws fewer stares than it did a decade ago and fewer people risk splashing unknown solutions. Eye protection hangs within reach, not behind a locked cabinet.

If suppliers published more transparent data, concerns would shrink. Many chemical companies now invest in sharing more complete safety documentation. Some research groups push for independent toxicology studies before adding specialty reagents into protocols. Until then, old rules still hold: treat every new powder with respect, use the best protection available, and keep up with the latest reports. Sodium 3-Morpholin-4-Ylpropane-1-Sulfonate might not rack up a record of disasters, but vigilance always pays off before something goes wrong.

Ask anyone in a lab, on a farm, or in manufacturing: purity isn’t just a number—it’s peace of mind. It’s easy to glance at a certificate that says “99.9% pure” and take it at face value, but every point after the decimal can make or break a process. Over the years, I’ve spoken with folks who learned the hard way what a fraction of a percent means when even tiny traces of something else end up in a reaction or on a field. No chemist or plant manager wants to see a costly batch fail over overlooked impurities.

High-purity chemicals don’t just serve chemistry enthusiasts. Pharmaceutical companies often push for purity levels above 99.99%. When the end product goes into the body, every microgram counts. Impurities in aspirin or antibiotics cause unwanted reactions or lower the medicine’s effectiveness. Food producers chase purity, too—nobody wants a “trace” contaminant to slip through into baby formula or bread.

Electronics firms tell a similar story. Silicon for computer chips must be squeaky clean, or the tiniest impurity turns into a massive headache—chips work slower, or whole wafers go to waste. During the pandemic, the world learned hard lessons about the fragility of supply chains and the pinch points that arise when quality falls short. Semiconductor shortages reminded us of the connection between chemical purity and technological reliability.

Words on a label hold little weight without reliable measurement. Labs rely on rigorous testing—gas chromatography, mass spectrometry, titration—to keep impurities in check. I’ve spent long days running sample after sample, knowing one misstep could let unwanted materials slip past. Good labs build their reputations on transparency, clear documentation, and a willingness to share data. This isn’t bureaucracy—it’s a safety net.

Across industries, certificates of analysis are more than paper. They should tie directly to traceable lots and include dates, methods, and analyst signatures. Without this detail, a “purity guarantee” isn’t worth much. Buyers have learned to ask for specifics: What’s the detection limit? Which impurities does the test check? Being hands-on and inquisitive often keeps disaster at bay.

International groups and governments set the bar—think USP for pharmaceuticals, ASTM for manufacturing, ISO for broad industry needs. These aren’t optional hoops; they’re the guardrails keeping processes safe and consistent. Hard-won lessons from history led to these rules. Before such standards, dangerous byproducts could end up in medicines or on dinner plates. People remember stories like those of contaminated heparin, and support these standards because trust is built slowly, bottle by bottle.

Mistakes and slip-ups still crop up. Data transparency needs constant reinforcement. Labs can invest in tougher audits, routine instrument calibration, and clear communication with clients. In my own work, regular proficiency testing—where a third party sends mystery samples—proved vital. Humility and openness about error rates and detection limits foster respect rather than skepticism.

Environmental impact from chemical production grows in importance, too. Purity can’t be chased recklessly; responsible firms choose greener reagents, and minimize waste while still hitting quality marks. Sustainability complements, rather than competes with, purity.

In the end, chemical purity touches everything from health and safety to cost and reliability. The next time someone asks about purity, they’re looking for more than a number—they’re looking for assurance grounded in evidence, built on trust, and proven every single day.

Sodium 3-morpholin-4-ylpropane-1-sulfonate shows up in many biochemistry labs, especially in buffer preparations. Lab hands might just call it “MOPS sodium salt.” Most often, this compound comes as a white, crystalline powder, dry and stable. Having handled this stuff across several research projects, I keep a respect for getting the basics of dissolution right. Jumping straight in without prepping well can waste time and even mess with data reliability down the line.

Start out by checking purity. Check the label, and if the batch sat open in humid air, it might draw some moisture. I weigh the powder on a calibrated digital balance. Accuracy matters; even tiny mismeasurements can throw off buffer performance in sensitive lab work.

I measure out the target mass in a clean, dry beaker. Most protocols use deionized water because tap water’s trace ions can mess with experiments, especially when working under tight pH windows. Pour about two-thirds of the desired final water volume into the beaker, not the whole thing right away. Stir with a magnetic stir bar rather than shaking—vigorous shaking sometimes leaves powder caked to the sides.

From personal experience, patience wins. The powder dissolves smoothly at room temperature, and heating usually isn’t required. But if cold or hard water slows things, a gentle warming on a low hotplate (never boiling) helps finish up without breaking down the compound.

Once all visible crystals disappear, I check pH using a reliable meter. Sometimes, MOPS buffers need pH adjustment—use small increments of HCl or NaOH with a plastic pipette, watching the value jog upward or downward. Skipping this step can lead to experimental headaches down the line. After pH adjustment, bring the solution up to final volume with more deionized water. Transfer to a clean storage bottle, label with concentration, pH, and prep date. Toss in a stir bar if long storage is planned, since some precipitation can still occur after a few days.

Every step protects data quality. Over-diluting or imprecise pH throws off molecular interactions in enzyme studies or cell culture. One project on protein crystallization taught me to double-check even simple protocols. Poor-quality solutions caused two wasted weeks before I tracked down mistakes in my buffer prep.

Chemical suppliers usually publish solubility information, but a quick calculation doesn’t cover every variable. If the solution looks cloudy or starts forming flakes over time, it’s wise to dump it and start over. Residues from old stir bars or dirty glassware can seed crystal growth that ruins a buffer.

Prepared solutions keep well at fridge temperature (about 4°C) for around a week. Microbial growth can show up if the bottle goes unsealed or if pipettes are double-dipped. If your lab keeps an autoclave handy, sterilizing the final buffer (letting it cool slowly) preserves shelf life but can alter pH slightly, making a quick recheck necessary.

Trust in simple, careful procedures means reproducible experiments—any scientist who’s had to repeat half a year’s work because of a lazy shortcut knows prevention beats cure, every time. Every bottle I mix, I remind myself that good science stands on careful hands and honest attention, not fancy equipment or lucky guesses.

| Names | |

| Preferred IUPAC name | Sodium 3-morpholin-4-ylpropane-1-sulfonate |

| Other names |

3-Morpholinopropanesulfonic acid MOPS |

| Pronunciation | /ˈsəʊdiəm θriː mɔːˈfɒlɪn fɔːˈɪl ˈprəʊpeɪn wʌn ˈsʌlfəneɪt/ |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | 113295-35-3 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | `CCCCS(=O)(=O)N1CCOCC1` |

| Beilstein Reference | 122427 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:9126 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL2007871 |

| ChemSpider | 21415984 |

| DrugBank | DB03742 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 03aa2b2d-dcd7-43b5-bb0a-57cc168bf47f |

| Gmelin Reference | 108670 |

| KEGG | C05673 |

| MeSH | D018492 |

| PubChem CID | 148154 |

| RTECS number | WY2575000 |

| UNII | Z3E6UYN10E |

| UN number | Not regulated |

| Properties | |

| Chemical formula | C7H15NO4SNa |

| Molar mass | 237.28 g/mol |

| Appearance | White to off-white powder |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | 1.29 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | Soluble in water |

| log P | -3.2 |

| Vapor pressure | <0.00001 mmHg (20°C) |

| Acidity (pKa) | 9.5 |

| Basicity (pKb) | 5.87 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | -38.1e-6 cm^3/mol |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.478 |

| Viscosity | Viscous liquid |

| Dipole moment | 6.5 D |

| Thermochemistry | |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 222.2 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Pharmacology | |

| ATC code | A09AB14 |

| Hazards | |

| Main hazards | Causes serious eye irritation. Causes skin irritation. May cause respiratory irritation. |

| GHS labelling | GHS07 |

| Pictograms | GHS07 |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | H302, H319 |

| Precautionary statements | P264, P270, P305+P351+P338, P337+P313 |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | 1-0-0 |

| Flash point | > 121°C |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 oral rat 5200 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | LD50 (Median dose): LD50 Oral Rat > 5,000 mg/kg |

| PEL (Permissible) | Not established |

| REL (Recommended) | 10g, 25g, 100g, 500g |

| Related compounds | |

| Related compounds |

MES CHES PIPES HEPES MOPS TES |