Potassium 3,3,4,4,5,5,6,6,7,7,8,8,8-tridecafluorooctanesulphonate, often referred to under its PFOS legacy name, didn’t arrive on the scene without a backstory. Early research into perfluorinated compounds gained traction in mid-20th century laboratories. Companies eyed these compounds for their ability to repel oil and water—making them gold for developing stain-resistant textiles and firefighting foams. PFOS-based chemicals became common in several industrial and consumer products before toxicology reports sounded alarms in the late 1990s, prompting urgent rethinking of their safety and a wave of regulatory action. A combination of persistent environmental detection, media coverage, and heightened legal scrutiny pushed researchers to take a hard look at production, health implications, and the molecules themselves.

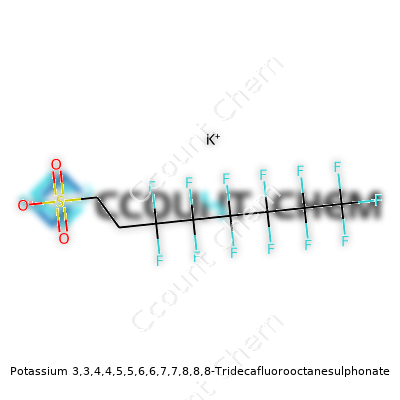

The potassium salt form of this fluorosurfactant always gets attention in technical circles for its strong surface activity. The chemical structure—a chain of thirteen fluorinated carbon atoms capped by a sulphonate group—lines up for applications where wetting, spreading, and chemical resistance matter. Potassium PFOS salts show up as off-white powders or granules that dissolve easily in water, enabling their infamous use in specialized fire-fighting foams, electroplating baths, and photographic materials. Manufacturers once prized it for giving products dirt, oil, and water resistance almost unmatched by other materials—but the tide has shifted as science revealed the environmental cost.

The physical and chemical behavior of potassium 3,3,4,4,5,5,6,6,7,7,8,8,8-tridecafluorooctanesulphonate comes from its fully fluorinated carbon chain. This molecule resists heat, acids, bases, and oxidation—a trait both boon and curse. Heat barely touches it, so it’s tough in high-temperature applications. Strong electronegativity of the fluorine atoms gives it both chemical inertness and hydrophobic-lipophobic nature, allowing the molecule to persist in aquatic and soil environments for decades or longer. Water solubility isn’t limited to the lab: once this salt leaches into the environment, it doesn’t break down or evaporate. So even after governments cracked down, legacy contamination keeps showing up in some surprising places around the world.

Selling or even shipping this material now means navigating a regulatory maze. Material Safety Data Sheets (MSDS) spill out every detail—CAS number 2795-39-3, molecular weight close to 538 g/mol, granular or powder morphology, storage recommendations at controlled room temperature. Labeling is explicit: hazardous to aquatic life, persistent in the environment, may accumulate in living organisms. Transporting potassium PFOS salts means using United Nations (UN) numbers and hazard labels, and regulations in Europe, North America, and Asia demand full disclosure of concentrations, possible impurities, and risk control measures. Labelling not only covers chemical identity but also warnings and disposal requirements, reflecting the legacy of misuse and environmental impact.

Production of the potassium salt starts with sulfonation of perfluorooctane, typically using oleum or another aggressive sulfonating agent, then neutralizing with potassium carbonate or potassium hydroxide. This process throws off hazardous byproducts that demand careful separation and responsible disposal. Even labs running small-batch syntheses face the challenge of controlling emissions to air and water. Halting releases of waste fluorinated byproducts cuts down risks for workers and neighbors. Production parameters always focus on achieving high-purity product—impurities compromise not only function in end products but also present further health and environmental risks. Today, much of this chemical comes from only a few licensed facilities, many running under government oversight to minimize environmental dispersal.

The story with perfluorooctanesulphonate is its stubbornness. Reactivity is low thanks to the strength of carbon-fluorine bonds along the chain. That said, under high-energy conditions—think plasma, UV irradiation, or extreme heat—it can degrade to yield shorter-chain perfluorinated acids and hydride fragments. Strong oxidizers and reductants barely dent the molecule under regular industrial conditions, one of the reasons cleaning up PFOS pollution needs high-tech remediation strategies. Across research labs, modification focuses on finding ways to break the chain or transform the molecule into less persistent forms, using methods such as advanced oxidation or electrochemical degradation, but simple substitution or hydrolysis rarely cause breakdown.

This compound shows up under numerous trade names and chemical synonyms. Older labeling called it potassium perfluorooctane sulfonate, often abbreviated as K-PFOS, or even its EINECS number, 220-471-2. In applications, it hides in lists of ingredients or process components with names like FC-95 or PFOSK. Different suppliers and regulatory agencies record it under slight name variants, but all point back to the perfluorinated sulfonate backbone. Staying aware of alternate names protects workers and regulators from missing its presence in legacy stockpiles or complex waste streams.

Handling potassium PFOS salt falls under some of the toughest chemical safety protocols in industry. Facility managers rely on closed systems and strong ventilation. Exposure controls hinge on personal protective equipment—gloves, goggles, and respirators. Air monitoring inside the workplace checks for vapor or dust contamination. Storage must exclude sources of moisture, heat, and incompatible materials like strong reducing agents. Standard procedure involves immediate reporting and containment of spills, and any cleanup integrates specialized absorbents and disposal as hazardous waste. Most importantly, safety training for personnel reminds everyone that chronic exposure brings long-term risks, including bioaccumulation, so casual habits have no place around materials like this.

Despite its reputation, potassium PFOS salt carved out a niche in industry, especially where resistance to oils, acids, and heat brings clear technical benefits. The fire-suppression sector once relied on it for aviation and oil-rig fires, and electronics manufacturing used it to etch circuit boards where nothing else worked as cleanly. Anodizing aluminum for aircraft parts, chrome plating for auto and aerospace, and even old photographic films banked on its unique surfactant powers. The downside is clear—every use led to environmental and human exposure. Alternatives now step up, but in some specialty applications the old material lingers while new chemistry catches up.

Research lab benches around the world remain busy, looking both forwards and backwards at potassium PFOS salt. Scientists run sophisticated analytics—liquid chromatography, mass spectrometry—to track it in waters, soils, foods, and even remote polar environments. The drive for new chemistry moves toward shorter-chain fluorinated compounds, but these too catch regulatory attention as their impacts emerge. Advanced water treatment pilot plants experiment with activated carbon, ion exchange, and high-energy plasma to remove PFOS from drinking supplies. Toxicology teams probe mechanisms of harm, gathering data on how low-level, chronic exposure links to thyroid problems, immune dysfunction, and developmental issues.

Toxicologists have dug deep into the question of what potassium PFOS salt does in animals and humans. These studies show the molecule resists metabolism in the body, circulating for years rather than days or weeks. Animal research ties exposure to liver enlargement, immune suppression, lowered birth weights, and cancer. Human epidemiology links its presence in blood samples to cholesterol elevation, altered hormone balances, and immune response shifts. Infants and children, still developing critical organ systems, carry greater risk. Legacy contamination near production sites and in places where firefighting foams washed into local waters spotlights the need for cleanup, monitoring, and long-term health tracking.

The future for potassium 3,3,4,4,5,5,6,6,7,7,8,8,8-tridecafluorooctanesulphonate doesn’t follow the old pattern. As more countries sign onto treaties like the Stockholm Convention, production and application shrink every year, replaced by new green chemistry and stricter supply chain audits. Still, countless tons persist in soil, water, and food chains, making remediation a giant global challenge. Industry and government need to work together, investing dollars and brainpower in novel cleanup, transparent reporting, and robust alternatives. If my own experience consulting in chemical safety tells me anything, it’s that once a persistent molecule like this goes global, problems last far longer than the profits. Replacing entrenched chemicals means not only inventing new products but also earning public trust—through open science, tough regulation, and by keeping people, land, and water safe for the next generations.

Potassium 3,3,4,4,5,5,6,6,7,7,8,8,8-Tridecafluorooctanesulphonate, which many in the lab call PFOS potassium salt, doesn’t pop up often in school chemistry textbooks. It shows up more in manufacturing settings and labs that deal with substances designed to handle heat, grease, or water. I first came across PFOS derivatives in a cleaning products research group, where their name alone was enough to turn a few heads.

Companies once used this chemical for coatings that kept carpets and upholstery stain-free and fabrics water-resistant. Some fire departments used to rely on it in aqueous film-forming foams (AFFF) for fighting fires involving oil or gasoline. The way PFOS-based products create a thin film that cuts out oxygen and snuffs out flames looked like magic when I watched a live demo during an industry workshop. In electroplating workshops, the potassium variant helped stop dangerous mist from rising off vats full of chrome.

Experience shows that once PFOS-related compounds end up in soil or water, they don’t just vanish. I spoke with a retired chemical engineer who remembers the days when regulatory talk about persistent chemicals sounded alarmist. He admits he underestimated how stubborn PFOS could be. Today, we know these compounds linger for decades, traveling through rivers, groundwater, and even showing up in fish hundreds of miles away from a plant.

There’s a reason regulators in the U.S., the EU, and Asia push for limits on PFOS and its cousins. Reports link PFOS with health effects such as changes in cholesterol, hormone interference, liver problems, and possible cancer links in test animals. No one likes learning that a chemical used to keep a jacket waterproof is swirling around in the blood of eagles or inside polar bears. Traces of PFOS now show up in drinking water in towns far from chemical plants, which has turned what felt like a distant industry problem into a daily news headline.

Bans and restrictions forced companies to scramble for alternatives. From where I stand, it’s clear that switching out PFOS-based chemicals doesn’t mean throwing quality out the window—but you can’t just slap on a replacement and hope for the best. Many fire departments invested in different foams, even though some firefighters grumbled about older foams’ effectiveness. Textile makers sought water- and stain-repellent coatings from silicon or hydrocarbon-based sources, spending months in testing just to keep their reputation safe. In plating shops, air filters and less persistent chemicals now help keep workers and the environment safer, although these options cost more.

I’ve heard some folks argue that careful control and monitoring could keep PFOS-type compounds in check. Others feel once a chemical proves to be this stubborn and widespread, it’s too risky for any non-essential use. From my time consulting with smaller manufacturers, I can say that most want clear answers: either reliable, safer substitutes or guidance on proper disposal so old stock doesn’t end up leaching into the ground.

Communities and industries still wrestle with PFOS potassium salt’s complicated legacy. It’s tempting to look for easy answers, but the story of this chemical turned up far more questions than anyone expected. Many people learned the hard way how a tiny part in a formula can leave a worldwide footprint. Now, the only real progress comes from honesty about the tradeoffs, stubbornness in the search for safer options, and respect for the long road to a cleaner environment.

Every so often, a chemical with a tongue-twister name starts popping up in news headlines, and people who never paid attention to chemistry in school begin to wonder about risk. Potassium 3,3,4,4,5,5,6,6,7,7,8,8,8-tridecafluorooctanesulphonate (let’s call it a PFOS salt) falls into that category. I remember skimming through research on persistent pollutants a few years ago, and this compound kept showing up linked to environmental fallout and controversies about Teflon, firefighting foams, and stain-resistant coatings.

People usually start asking about PFOS salts once they find out they don’t break down in the environment. They stick around, showing up in groundwater, rivers, even human blood samples—you name it. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) tracked PFOS in thousands of Americans, confirming that it’s pretty much everywhere.

So what does that mean for people’s health? Animal studies, along with plenty of lab evidence, point to immune suppression, some liver damage, shifts in cholesterol, and (in high doses) developmental effects. Human data often trails behind because most people aren’t exposed to huge quantities at once, so the question keeps coming up about what low or steady exposure does over years.

People living near factories where PFOS-related chemicals have been used or disposed of face the greatest risk. Even if your house doesn’t sit next to a chemical plant, products treated with PFOS-based coatings often end up in dumps and leach into local water supplies. In my own community, PFOS scare came up after a water district ran a round of voluntary testing. The result: levels above the health advisory. Public meetings got heated. Folks demanded answers from local officials about cleanup, health risks, and what could honestly be done.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency pegged a very low lifetime health advisory level for PFOS in drinking water, dropping expectations to just a handful of parts per trillion. That’s not because a little bit will start a health crisis, but out of caution—these chemicals stick around, so tiny amounts add up.

The science points to “forever chemicals” like potassium PFOS as possible hazards and supports cutting off exposure where possible. I’ve watched cities replace water filters, close off contaminated wells, and test soil after decades of silent buildup.

Fixing the problem often means pushing for more research, advocating smarter chemical policies, and tracking where these compounds have turned up. I’ve talked with a few scientists who say that alternatives exist for many uses, but switching out old habits takes serious attention and sometimes higher cost.

For communities, the first step often involves building trust that testing happens honestly and results won’t get brushed aside. Health agencies keep checking blood levels and sharing advice about safe water. More importantly, holding chemical makers and buyers to account nudges industry away from persistent and toxic options. If history teaches anything, it’s that public transparency and regulatory pressure have moved the needle more than market forces alone.

Chemicals like Potassium 3,3,4,4,5,5,6,6,7,7,8,8,8-Tridecafluorooctanesulphonate demand a certain level of respect. I picked up a healthy caution for hazardous substances in my early laboratory days—one spill, one wrong cap, or one mix-up often meant more than a broken rule. It could put someone in the hospital or pollute a whole area. This compound doesn’t have the notoriety of mercury or benzene, but it brings its own quirks to the table. It belongs to the big, tough world of perfluorinated chemicals, which stay stubbornly intact in the environment.

Potassium 3,3,4,4,5,5,6,6,7,7,8,8,8-Tridecafluorooctanesulphonate plays a role in firefighting foams, manufacturing, and surface treatments. All that industrial muscle means people bring it into labs, factories, and storage rooms. Leaving safety as an afterthought doesn’t cut it. Stories have emerged about perfluorinated chemicals leaking and contaminating soil and water—sometimes for decades. They resist breakdown through most normal processes. According to EPA reports, gaps in chemical storage often lead straight to environmental crises.

I remember learning that what matters is sealing, temperature, and compatibility. This compound doesn’t flare up at the drop of a hat, but reacting it with strong acids or bases brings problems, and exposure to heat or sunlight may degrade its packaging. I always put emphasis on tight sealing—original containers, screw caps in good shape. No sense risking a spill due to a strip of tape or a flimsy bag. Sturdy, labeled containers stop confusion on busy shelves. There’s a reason lab pros repeat it so often: clear labeling keeps accidents away.

Dry, cool, and well-ventilated storage spaces serve everyone best. I stick with shelving away from sunlight, out of the heat, and without humidity. Refrigeration stays overkill for this substance, but a climate-controlled room makes sense in most labs. Humidity opens the door to clumping or caking for certain powders and salts. Remember those warning labels that say “keep container tightly closed in a dry and well-ventilated place”? They’re not just legal boilerplate—they come from decades of real incidents.

Storing Potassium 3,3,4,4,5,5,6,6,7,7,8,8,8-Tridecafluorooctanesulphonate doesn’t end with the right shelf. Leakage and spills need easy cleanup. From firsthand experience, I always keep spill kits within reach—absorbent pads and neutralizing agents make a difference in a pinch. Personal protective equipment isn’t optional either. Gloves, goggles, and lab coats mean less direct contact and quicker cleanup.

Waste isn’t something to push aside. Safe disposal through a licensed hazardous waste handler reduces personal and environmental risk. The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health urges proper management from use through final disposal, not just safe storage. That follows the E-E-A-T principle—safeguarding the environment and the workers who handle these chemicals.

Demand a logbook. Document each time this substance enters and leaves storage. With accidents, confusion comes quickly, so clear records support accountability. Routine checks of inventory and storage conditions can expose slow leaks or unnoticed container damage. Change starts with habits like these. Sharing safety practices among labs and manufacturing spaces means better protection, stronger compliance, and less chance of repeating the environmental slip-ups found across chemical history.

Standing in the middle of a chemical facility, that cold feeling creeps over your neck once you spot an odd stain and realize you’re staring at a spill of Potassium 3,3,4,4,5,5,6,6,7,7,8,8,8-Tridecafluorooctanesulphonate. This mouthful of a molecule, better recognized by people who’ve spent years in labs that deal with surfactants and specialty chemicals, deserves serious caution. It might help factories and various industries push their processes forward, but the substance can bring real problems the moment it escapes its containment.

My first brush with a fluorochemical product like this didn’t come with a full safety data sheet review. Early in my career at a manufacturing site, I watched as a handful of workers scrambled—no one sure about exactly how to respond. This compound doesn’t just dissolve or break down quickly. Once it slips into a drain or mixes with soil, it lingers there for years and can carry through water to places no one even thought about protecting.

Much of the world’s health guidance circles back to these so-called “forever chemicals”—fluorochemicals that have turned up in drinking water supplies and built up in fish, animals, and human blood. The US Environmental Protection Agency and the European Chemicals Agency have placed strict regulations on these compounds. These facts shape how we ought to respond, not just for regulations, but for our own safety and that of workers around us.

If I see a spill on a shop floor, there’s often a split second where someone wants to grab a mop and bucket. Skip that. The right step starts with cordoning off the area. No one who isn’t in full gear—think gloves resistant to chemicals, protective suits, splash-proof goggles—should get near the mess. The sloppier the response, the easier it is for a bit of powder or solution to find a crack or drain, and that’s all it takes for this chemical to start its long journey through the environment.

On my better spill days, we’ve poured absorbent materials—think clay-based products or vermiculite—right over the substance. These keep the fine particulates from turning airborne or washing into pipes. Standard rags are a poor idea, and sending anything through a regular wash only spreads the problem. Collected waste needs a container marked specifically for hazardous waste management. This part matters: the chemical doesn’t go into regular dumpsters; it needs disposal via facilities prepared to handle perfluorinated substances, who incinerate or process the waste without allowing anything to seep away.

Training plays a huge role here. Team members don’t get ready by osmosis; they need regular drills and refreshers. The folks who develop the safety sheets and Standard Operating Procedures don’t live in a vacuum, so it takes feedback from real incidents to push for updates that everyone trusts. Each close call refines those steps—so staff don’t miss something critical in a split-second decision.

Spill kits designed for fluorinated chemicals ought to stand within arm’s reach in any place where these products get handled. Daily inspections of storage containers, labels that stand out, and clear records keep lapses from becoming real incidents. As much as we want quick answers, spills teach humility. The work never finishes, and that lingering sense of responsibility follows anyone, long after the cleanup ends.

Potassium 3,3,4,4,5,5,6,6,7,7,8,8,8-tridecafluorooctanesulphonate — that’s a name with some serious weight behind it. The chemical formula for this compound is C8HF13KO3S. Stripping that down, the backbone comes from an eight-carbon chain, saturated at spots with fluorine atoms, and it ends with a sulfonate group that’s balanced by a potassium ion. In the real world, folks often call this compound PFOS potassium salt.

Imagine a carbon chain dressed up in fluorines so much that regular chemistry just can’t wear it down. Each carbon from position 3 to 8 holds two fluorine atoms, except the tail, which packs three. All those fluorine atoms bring fire-resistant and water-shunning qualities. The sulfonate group — SO3 — has a potassium ion riding shotgun to even things out. It’s not a household name, but lots of consumer products worked it into fabrics, food wrappers, or firefighting foams.

Talking about chemical structure might sound dry, but this chain, heavy with fluorines, gives PFOS the stubborn durability that makes it both useful and a headache. The strong carbon–fluorine bonds resist heat, acids, and breaking down in nature. That’s a dream for waterproofing your favorite jacket, or keeping greasy popcorn butter from leaking through the bag. It’s less of a dream when these molecules turn up in soil, water, or even our blood, sticking around for decades.

I remember seeing PFOS stories crop up in science magazines — back then, no one really talked about bioaccumulation. Now, researchers find traces of these compounds from polar bears to tap water. The chemical makeup basically hands these molecules a free pass: they slip through regular water treatment and stick around in places where chemical companies never expected them to go.

That stubbornness, all tied to the chemical structure, led health authorities to pay close attention. PFOS can hang around in living bodies, not just the environment. Studies show links to cholesterol changes, disruptions in hormones, and developmental issues in kids exposed to higher levels. It’s unsettling to think a spill or heavy use from decades ago still echoes through today’s ecosystem and possibly our health.

The durability comes from that fluorinated carbon backbone, which doesn’t break down with UV light or regular microbes. That’s rare for synthetic chemicals, and it shaped the response from watchdog groups, regulators, and local communities. Once the dangers of these compounds surfaced, governing bodies like the US Environmental Protection Agency and the European Chemicals Agency rolled out strict controls.

Taking on persistent compounds like PFOS means digging deep, both into chemistry and policy solutions. Activated carbon filtration systems can pull out PFOS from water supplies, and ongoing research looks at ways to finally break those tough carbon-fluorine bonds. People also push for greater transparency and full disclosure from manufacturers.

A messy problem needs real, science-based teamwork: better water testing, health monitoring, pressure on industry to shift toward safer substitutes. Focusing on risk reduction and cleanup means nobody treats a complicated name on a label as “out of sight, out of mind.” People and ecosystems deserve to know exactly what’s lurking in the materials around them, and a closer look at chemical structure brings those answers home.

| Names | |

| Preferred IUPAC name | Potassium 2,2,3,3,4,4,5,5,6,6,7,7,7-Tridecafluorooctane-1-sulfonate |

| Other names |

Potassium perfluorooctanesulfonate Potassium PFOS |

| Pronunciation | /pəˈtæsiəm ˌtraɪdiːkəˌflʊəroʊˌɒkˈteɪnˌsʌlˈfəneɪt/ |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | 756-13-8 |

| Beilstein Reference | 3848327 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:64135 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL4294415 |

| ChemSpider | 63219 |

| DrugBank | DB11108 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 03e2f6d6-87db-452b-b8e6-007b462b6843 |

| EC Number | EC 221-995-6 |

| Gmelin Reference | 57738 |

| KEGG | C18236 |

| MeSH | D000072620 |

| PubChem CID | 24836306 |

| RTECS number | TD1275000 |

| UNII | WQK2237X0X |

| UN number | UN3077 |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | DTXSID8025724 |

| Properties | |

| Chemical formula | C8F13KO3S |

| Molar mass | 538.22 g/mol |

| Appearance | White powder |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | 1.8 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | Soluble |

| log P | 4.8 |

| Vapor pressure | Negligible |

| Acidity (pKa) | -3.31 |

| Basicity (pKb) | -5.3 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | -45.1×10^-6 cm³/mol |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.312 |

| Dipole moment | 3.49 D |

| Thermochemistry | |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 636.6 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -1564.61 kJ/mol |

| Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) | -5764.8 kJ mol-1 |

| Pharmacology | |

| ATC code | A16AX13 |

| Hazards | |

| Main hazards | May cause damage to organs through prolonged or repeated exposure. Harmful if swallowed. Causes serious eye irritation. Causes skin irritation. May cause respiratory irritation. |

| GHS labelling | GHS02, GHS07, GHS08 |

| Pictograms | GHS07,GHS08,GHS09 |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | H413: May cause long-lasting harmful effects to aquatic life. |

| Precautionary statements | Precautionary statements: P261, P273, P280, P304+P340, P312, P337+P313, P403+P233 |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | 1-0-1-ℵ |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 Oral - Rat - 599 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | LD50 (median dose): Rat oral >2000 mg/kg |

| NIOSH | WFJ9EW2VV5 |

| REL (Recommended) | 0.01 mg/m3 |

| IDLH (Immediate danger) | No IDLH established. |

| Related compounds | |

| Related compounds |

Perfluorooctanesulfonic acid Lithium 3,3,4,4,5,5,6,6,7,7,8,8,8-tridecafluorooctanesulphonate Sodium perfluorooctanesulfonate Potassium perfluorooctanoate |