Chemistry doesn't often introduce paradoxes in how metals interact with organic acids, but the appearance of Lead(II) bis(methanesulfonate) in scientific catalogs traces back to the rise of specialty salts in battery and electroplating research across the late 20th century. Industrial chemists looked for salts with greater solubility in water and compatibility with non-oxidizing conditions—something the tired old lead acetate rarely delivered. Methanesulfonates popped up as promising candidates, blending organic and inorganic characteristics to fill the gaps traditional salts left open. Researchers in Europe and Asia drove much of the early exploration, motivated by cleaner, more controllable lead sources for analytical chemistry and the electrolytic cell.

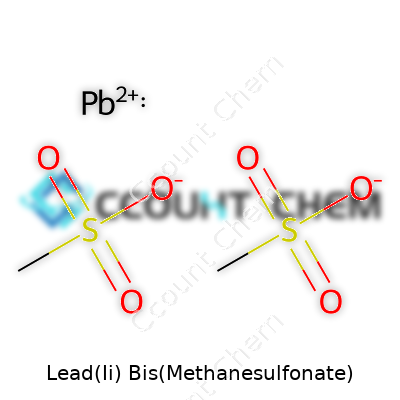

Lead(II) bis(methanesulfonate) appears as a white or near-white powder, with a structure built from two methanesulfonate anions per lead cation. The chemical formula hits as Pb(CH3SO3)2. Its ready water solubility and moderate acidity shape it into a favorite for anyone working with lead-based electrolytes. Commercial suppliers usually target labs and pilot plants exploring advanced batteries, as well as academic teams picking apart its electrochemical behaviors.

Most labs recognize this salt by its crystalline powder appearance. It dissolves quickly in water, and from direct handling, leaves a slippery trace like many sulf(on)ates. The precise melting and boiling points hang on the purity, but expect decomposition before vaporization. Its low vapor pressure keeps the working area safer, though measurable amounts of lead can migrate through solution. Often, the material forms slightly acidic solutions due to the sulfonate group. One key point: stability doesn't falter in air, but the substance stays sensitive near open flames or under strong bases and oxidizers.

A technical spec sheet for this compound usually spells out percent lead (around 36-38%), percent methanesulfonate, and limits on heavy metals like cadmium and arsenic. Purity often ticks above 98%. Standard packaging comes in plastic or glass vials, each labeled with the product code, batch number, concentration, and the mandatory hazard pictograms—skull and crossbones for acute toxicity, exclamation point for general hazard, and the environmental warning. In line with modern practice, barcoding and QR codes link buyers to the relevant safety documentation, which must be reviewed before use and every time a new batch arrives.

Synthesizing Lead(II) bis(methanesulfonate) isn't flashy, but reproducibility sorts the experienced chemist from the greenhorn. A common route uses lead(II) oxide or carbonate, added portionwise to warm aqueous methanesulfonic acid. Gentle heating finishes the reaction, giving a clear solution. Evaporation, either gentle or under vacuum, pulls out the crystalline product. Any colored byproduct signals contamination—a sign to check either reagent quality or lab glass rigor. Purification, if necessary, proceeds via recrystallization from water, and the yield generally surpasses 90% in well-run setups.

This lead salt behaves with predictable chemistry in the hands of both student and professional. It swaps anions with halides or carbonates, forming insoluble precipitates—an old trick in qualitative analysis. It readily undergoes redox reactions in electrochemical cells, which accounts for its use in battery research and electrorefining. Treating it with ligands like EDTA chelates out the lead for titrimetric analysis. Its behavior in organic solvents tells you plenty about the polar character of the methanesulfonate group, with most researchers finding that water or polar alcohols suit their needs.

You might spot this compound under several names: "Lead(II) methanesulfonate", "Lead dimethanesulfonate", or for those wading through regulatory paperwork, "Methanesulfonic acid, lead(II) salt". CAS registries and European chemicals regulations shorthand it as 17570-76-2. Specialty chemicals catalogs tend to phrase it as the "bis" salt to avoid confusion with mono-substituted competitors, and some trade names attach a prefix or suffix referencing the purity grade. Skimming past old journal articles, lead(II) methylsulfonate sometimes pops up, especially from the ‘80s and ‘90s.

Work with this compound requires respect for its risks. Toxicity—especially for neurological and developmental health—is the main issue. Lab protocols demand gloves, safety goggles, and fume hoods at all times; even minor spills trigger specific decontamination routines. The global shift away from routine lead use means that storage and disposal rules have grown tougher. Waste goes into marked, double-contained lead hazard drums, never into the general trash or sink. Regular training reminds staff how fast low-level exposure accumulates risk, particularly if it touches skin or contaminates lunchrooms and offices. Air monitoring might come up in larger industrial settings, and surface wipe tests check for lingering dust after cleanup.

Though most folks won't see Lead(II) bis(methanesulfonate) on the job, its applications keep growing in research and niche manufacturing. Electroplating with methanesulfonate-based baths beats acetate or nitrate for even metal coverage and lower environmental acidification. Modern flow-battery experiments tap this salt to explore higher voltage, longer cycling potential. Its role as a standard or reagent shows up in analytical testing of soils and wastewaters, where lead recovery matters. Some folks investigate its interaction with polymers for new materials, and a few teams in catalysis research probe how lead-methanesulfonate catalysts operate at lower temperatures or unique solvent conditions.

Over the last decade, academic research has paid fresh attention to lead methanesulfonate, mostly due to the wider search for cleaner rechargeable battery systems. As teams try to boost efficiency and lifetime, switching to methanesulfonate salts reduces side-reactions. Publications from Asia, Europe, and North America dive into electrolyte optimizations with this compound, seeking less corrosive, more recyclable battery systems. Labs at major universities compare the performance of these salts under real cycling conditions. Besides electrochemistry, there's also exploration into low-temperature precipitation and selective recovery from e-waste using methanesulfonate-based solutions, promising steps toward circular chemistry for toxic metals.

Every lead compound raises red flags, but studies on solubility and biological uptake show some differences in the threat level of the methanesulfonate salt. Its high solubility means exposure risks ratchet up compared to less dissolvable forms—fast absorption dominates concerns in spills and lab mishaps. Rodent studies point to the same neurological and organ-specific toxicity as other soluble lead salts. The compound persists in soils and water if released, and remediation runs into the same roadblocks that plague other soluble metals. Toxicological data sets keep growing but drive home a simple truth: safe handling and strong barriers from the lab bench to the waste room stay non-negotiable.

Looking ahead, tighter regulations on lead continue to clash with the need for high-performance materials and research on energy storage. Lead(II) bis(methanesulfonate) could keep finding a spot in specialized batteries with higher operational standards, buffered by improvements in recycling and containment. Advances in chelation chemistry and waste recovery hold some promise for closing the loop—limiting not just final emissions, but also exposure throughout the compound’s lifecycle. Researchers aim for drop-in replacements, yet until then, expect Lead(II) bis(methanesulfonate) to hang around in high-tech labs and regulated industries, always with one eye on performance and the other on health and safety.

Lead(II) bis(methanesulfonate) isn’t something most people hear about day to day, but its place in industry—especially in batteries—is real and significant. People making industrial batteries for things like backup power, telecom towers, or even renewable energy storage often turn to this compound. Unlike more familiar forms of lead, this one dissolves in water, and that property gives battery makers more control over how the lead moves and settles onto battery plates during production. Consistent coating means better batteries, and better batteries keep businesses running and lights on in storms.

I’ve met engineers who swear by it for manufacturing. They prefer it because it delivers a cleaner process than using older lead salts. If you’ve ever visited a battery plant, you’ll see there’s always a layer of dust to fight off. Using lead(II) bis(methanesulfonate) can reduce some of that mess, cutting back on cleaning and keeping the air safer for the people working on the floor. In my conversations with industry professionals, many mention fewer stoppages and longer equipment life when they use chemicals that don’t clump or leave behind as much residue.

Nobody forgets that lead is toxic—including the folks who handle these chemicals daily. Regulatory groups worldwide watch carefully, and communities pay attention to local pollution reports. Every new chemical in the factory brings questions: Will it lower emissions? Does it make handling lead safer? Lead(II) bis(methanesulfonate) allows some companies to cut back on other, riskier chemicals, which matters in places where regulations keep tightening. Still, the fundamental hazards of lead-based compounds don’t disappear—companies need serious checks, like strict ventilation and regular blood tests for workers.

Battery recycling has started to pick up steam as more batteries reach the end of their lives, especially after years of storage on solar farms or inside large data centers. Chemicals like lead(II) bis(methanesulfonate) can sometimes help recyclers pull more productive material from old batteries, making recycling a touch more efficient. But that is only one piece of the puzzle. In practice, I’ve seen recyclers struggle to keep up with the sheer volume of batteries coming in. The process still generates lead waste, which needs careful handling to avoid contaminating water or soil.

Shifting to safer compounds has become a theme across manufacturing. Lead(II) bis(methanesulfonate) might offer a health and environmental edge over some alternatives, but it doesn’t mean manufacturers get a free pass. Real progress happens when companies invest in closed-loop systems, train their workers properly, and stay ahead of regulations instead of playing catch-up. New technology—better filters, smarter containment, automated handling—can bring exposure risks down further. Places that have spent money on modernizing plants tend to see fewer accidents and healthier staff.

Talking about specialized chemicals can feel distant. Yet the power running the hospital, the server farm, or even the pumps in a water system may depend on batteries made using compounds like lead(II) bis(methanesulfonate). Decisions made about which chemicals go into manufacturing ripple outward and touch more lives than most realize. People working the line, neighbors downwind of a plant, families living near a landfill—they all have a stake in safe, smart handling of substances in industry.

Walking through the world of inorganic chemistry, I’ve seen plenty of names that ring complex but point to something practical. Lead(II) bis(methanesulfonate) sounds daunting, but its formula boils down to a straightforward relationship: each lead ion links to two methanesulfonate ions. So, we get Pb(CH3SO3)2.

The journey of methanesulfonate with lead often starts in the specialty chemical sector. Manufacturers pick such compounds because of their solubility and clean reactions. Electroplating counts on this combination. Lead(II) bis(methanesulfonate) helps deliver a uniform lead layer without the headaches brought on by some harsher alternatives. Sulfate and nitrate salts bring along more side reactions and waste.

Down in batteries, it’s a similar story. Lead acid batteries play a big role in backup systems, vehicles, and renewable storage. Researchers often check alternatives for cleaner handling and more stable performance. Methanesulfonate salts make life easier since they dissolve well and don’t mess up downstream processes.

Time spent in labs teaches a deep respect for lead’s darker side. Lead exposure links to nervous system harm, organ damage, and developmental problems in kids. Mistakes in handling can haunt a community for years. Even though methanesulfonate isn’t volatile or particularly hazardous by itself, coupling it with lead calls for strict attention. Each shipment, lab bench, or storage drum must keep to safe handling rules. Personal protective equipment doesn’t just check a box — it protects everyone down the line, from worker to end consumer.

Regulation seems strict, but for good reason. The EPA, OSHA, and similar groups in Europe track lead’s movement like hawks. Any chemical house using or making Pb(CH3SO3)2 faces heavy paperwork and continuous monitoring. Shortcuts don’t just cost fines; they damage reputations and risk real lives.

Not every company sticks to lead bis(methanesulfonate). Environmental credentials push industries toward less toxic metals or greener electrolyte choices. Tin, silver, or even organic salts cut down on environmental fallout. Still, some jobs require those lead-specific properties — low melting point, high density, and steady conductivity. Until something better steps up, industries manage risks by recycling waste, keeping closed systems, and investing in worker training.

There’s room for hope. Research keeps unearthing safer candidates or tweaks that cut down on free lead exposure. Methanesulfonate chemistry actually comes from this push for safety, replacing harsher anions that linger and pollute. Cleaner recovery and recycling processes have started turning the tide for heavy metal chemistry.

Chemistry classes taught the basic formula, but work in the field spelled out the bigger picture: Every decision on chemical use touches people, water, and soil, far beyond the flask. Pb(CH3SO3)2 sits at the crossroads of industry progress and public responsibility. Balancing innovation and accountability keeps the better solutions coming.

Lead(II) bis(methanesulfonate) might sound like a mouthful, but it’s just one of many industrial compounds built on lead. The chemical’s main use shows up in the world of batteries, especially advanced lead-acid or flow batteries, where efficiency and cost matter. Behind the technical jargon lies an issue familiar to anyone who follows public health: lead exposure can be toxic.

Lead has a long and troubled history as a public health threat. There isn’t a “safe” form of lead, no matter how stable the compound might seem in a lab. Once it ends up in the wrong place — air, water, soil, or inside the body — trouble follows. Lead attacks the brain, kidneys, and other organs. Kids carry more risk than adults. Lifelong learning problems and behavioral issues might start with a small amount of dust.

A few decades back, public health experts pushed for lead to disappear from gasoline, paints, and pipes. The world saw improvements after these bans. That experience sticks with me. Our family home had paint flakes that tested positive for lead in the ’90s. Cleanup and buffer zones kept young cousins safe, but that experience taught us that vigilance matters with any lead compound, not just the infamous ones.

Working directly with this compound brings exposure risks. Safety data sheets show clear warnings: avoid skin contact, don’t breathe in dust or fumes, keep the material away from food and drinks. Inside an industrial facility, lead(II) bis(methanesulfonate) can break down and create lead dust or vapors, especially when companies cut corners on containment or air filtration. The difference between a safe workstation and one laced with dust comes down to strict handling and good training.

Once it escapes into the environment, the compound doesn’t vanish. Rain and poor storage wash residues into waterways. Food chain contamination kicks into gear. People who don’t even work with these materials can face exposure through tainted water, crops, or accidental contact.

Major agencies, including the CDC, EPA, and WHO, agree that all forms of lead threaten human health. It doesn’t matter if it’s in a new battery salt or an ancient pipe joint. Blood lead levels above 5 micrograms per deciliter are enough for concern in kids, with more severe effects creeping in as levels rise. Industries sometimes point to lower solubility in specialized compounds, but research shows chronic exposure can still leach dangerous levels.

Industries need strict protocols for workers, better air monitoring, tough personal protective equipment, and real investment in cleanup technology. Community education campaigns help people recognize the risks of lead exposure, not just from peeling paint but from new industrial byproducts. Governments should enforce storage and cleanup rules, and users must dispose of all lead salts responsibly.

Research into safer battery materials deserves funding so future generations don’t inherit more lead-related health crises. Simple habits like double hand washing and strict separation of work clothes can make a real difference, as I saw in a family friend who brought dust home from a metal finishing shop years back. Avoiding shortcuts keeps families and neighbors out of harm’s way.

Lead-based chemicals have a reputation for causing serious harm when managed carelessly. My time working with industrial labs showed me how even seasoned professionals take extra care around salts like Lead(II) Bis(Methanesulfonate). One false move can mean long-term contamination or health risks no one should ignore. It’s not just the lead ion that’s a problem—sulfonate salts creep into air, water, and skin faster than people think. People underestimate the compound’s reach. Personal experience taught me to focus on small daily habits: double-checking seal integrity and keeping track of who touched what.

It’s tempting to toss chemicals into whatever container is handy, but this salt demands a tougher approach. Storing Lead(II) Bis(Methanesulfonate) in clean, airtight plastic or glass containers keeps out air and moisture. I’ve used thick-walled HDPE bottles for years, after watching glass get chipped once too often. Polypropylene and polyethylene stand up to the salt’s chemical bite, keep powders dry, and block most vapor leaks.

People sometimes ignore labeling. Sloppy labeling leads to mix-ups, so every container should have clear, typed labels showing contents, concentration, hazard statements, and dates. Permanent markers and old masking tape make for hard-to-read labels that fade and confuse new staff. Print labels and use chemical-resistant tape, every time.

This compound doesn’t belong on an open shelf. High humidity triggers clumping and speeds up corrosion of nearby metal surfaces. I’ve opened jars that sat too near a sink and found them fused together in one rock-hard mass. Store in a well-ventilated, low-humidity storeroom, away from direct sunlight, and always out of reach of heat sources. Chemical storage cabinets with spill trays and ventilation fans keep the workspace safe, not just tidy.

Lead(II) salts should stay away from food, beverages, and personal effects. In one incident I observed, a lunch left in the same room as lead salts led to a needless panic and a whole day’s lost work for hazardous waste cleanup. Designating a strict chemical-only zone makes cross-contamination far less likely.

Lead finds its way onto skin and clothing in places people forget—bag handles, doorknobs, notebook covers. Proper PPE means lab coats, gloves, and, for powders, sometimes a respirator. Over-sleeves and disposable gloves stay by the cabinet, with no exceptions. Spillage is inevitable; secondary containment trays catch drips, and regular inspections keep surfaces clean. A forgotten spill can expose workers for years.

Long-term safety depends on documentation. Each batch gets recorded—how much, where it went, how it left. Some labs I worked in set up electronic logs so everyone knew the status of each chemical at a glance. Lead waste never goes down the drain; all spent compounds land in dedicated hazardous waste containers, then off to a licensed disposal company. Regular spot checks help keep the danger at bay and assure regulators that management pays attention.

Chemical safety improves with sharp habits. Automation and simple digital tracking cut down on mistakes. Frequent in-house training drives home the importance of these simple practices. Getting better storage cabinets won’t help if habits stay lax. Open conversations about near-misses create a culture where speaking up is routine, not embarrassing. In the end, keeping any lead compound—including Lead(II) Bis(Methanesulfonate)—safe comes down to preparation, vigilance, and doing the right thing each day, not just during audits.

Lab work and industry both keep a close eye on chemical purity, especially with compounds like Lead(II) Bis(Methanesulfonate). This material sees a lot of use in the battery industry and in surface plating, so all sorts of strict standards follow it from one procurement sheet to the next. Chemists who have run into low-purity stocks learn quickly how much trace contamination influences performance, especially in electrochemical systems. The fact is, a little iron, copper, or silica can throw months of research or production off course.

Most manufacturers mark Lead(II) Bis(Methanesulfonate) at 98 to 99.5% purity for commercial-grade stock. This level meets the needs of most battery research and electroplating tasks. Companies like Alfa Aesar, Strem, and several specialists out of East Asia publish this figure as standard. Lab catalogues list the breakdown plainly: 0.5% or less traces, usually including alkali metals and bits of unreacted precursors.

Sometimes, buyers who want higher performance materials get offers for 99.9% pure stock, which the market calls “high purity” or, occasionally, “electronic grade.” Besides stricter impurity limits, these options come with certificates of analysis and supply-chain documentation. My conversations with purchasing agents and researchers confirm that jumping from 99 to 99.9% hikes the price, yet doesn’t always guarantee less noise in really sensitive electrochemical work. I've seen projects at university labs struggle more with shipping containers leaking dust, rather than actual impurity content from the syntheses.

Production techniques make a major difference. The wet synthesis method, favored for price and scale, sometimes leaves tiny residues of methanesulfonic acid or lead carbonate. Some suppliers run product through multiple recrystallization steps, or push it through ion-exchange columns. In my own work, crude runs of Lead(II) Bis(Methanesulfonate) needed at least two washes to settle out visible raw material. That little extra time spent filtering paid off during testing—fewer odd peaks and more consistent cell runs.

Quality control can slip, especially with non-mainstream suppliers. Industrial buyers tell me they see a lot more variance in drums sourced from unaccredited companies. Inconsistent purity not only affects the intended chemical process, but also crops up as unexpected color changes or clumping, forcing troubleshooting sessions that eat into budgets.

People rely on independent labs for sample verification. Standard tools like ICP-OES, titration, and spectrometry catch lead content that veers from spec. In battery research, even a 0.2% bump in unwanted metals can drop cycle life or efficiency. After talking with old-timers in battery pilot plants, the rule that sticks—never trust a purity sticker without backup data—proves itself with every new batch.

Simple steps often improve results. Filtering, recrystallization, and even basic drying over silica gel works wonders for suspect material. Many researchers keep a log of lot numbers and track how changes in purity link to experimental noise. In industry, long-term contracts with reputable suppliers and third-party spot checks help prevent surprises.

In my experience, the posted purity is a starting point, not an absolute. Getting the most out of Lead(II) Bis(Methanesulfonate) means checking, rechecking, and not cutting corners with vendor selection or lab prep.

| Names | |

| Preferred IUPAC name | lead(II) methanesulfonate |

| Other names |

Lead(II) methylsulfonate Lead dimethanesulfonate |

| Pronunciation | /ˈliːd tuː bɪs ˌmɛθ.eɪnˈsʌl.fə.neɪt/ |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | 17570-76-2 |

| Beilstein Reference | 3903132 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:91249 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL3988961 |

| ChemSpider | 8143494 |

| DrugBank | DB14674 |

| ECHA InfoCard | EC Number 401-750-5 |

| EC Number | 208-939-6 |

| Gmelin Reference | 131134 |

| KEGG | C18647 |

| MeSH | D016899 |

| PubChem CID | 24866195 |

| RTECS number | OV8400000 |

| UNII | 3S1S550J0L |

| UN number | UN3077 |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | DTXSID6024761 |

| Properties | |

| Chemical formula | Pb(CH3SO3)2 |

| Molar mass | 449.42 g/mol |

| Appearance | White solid |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | 3.54 g/cm3 |

| Solubility in water | Soluble |

| log P | -3.2 |

| Vapor pressure | <0.1 mmHg (20 °C) |

| Acidity (pKa) | -3.0 |

| Basicity (pKb) | -3.7 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | -74.0e-6 cm³/mol |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.580 |

| Dipole moment | 0 D |

| Thermochemistry | |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 322.2 J mol⁻¹ K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -697.3 kJ/mol |

| Pharmacology | |

| ATC code | V03AB56 |

| Hazards | |

| Main hazards | May cause cancer; Harmful if swallowed; Causes damage to organs through prolonged or repeated exposure |

| GHS labelling | GHS05, GHS07, GHS08 |

| Pictograms | GHS05,GHS07 |

| Signal word | Danger |

| Hazard statements | H302, H332, H360, H373 |

| Precautionary statements | P261, P273, P280, P302+P352, P305+P351+P338, P310, P405, P501 |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | 2-0-0 |

| Explosive limits | Non-explosive |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 Oral Rat 468 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | LD50 (median dose) Oral Rat: >2000 mg/kg |

| NIOSH | JN8225000 |

| PEL (Permissible) | 0.05 mg/m3 |

| REL (Recommended) | 0.015 mg/m3 |

| IDLH (Immediate danger) | Unknown |

| Related compounds | |

| Related compounds |

Methanesulfonic acid Lead(II) nitrate Lead(II) acetate |