Chemists have worked with sulfonic acids for over a hundred years, but the journey towards focused study of ethanesulfonic acid methyl ester came in lockstep with the rise of organic synthesis through the 20th century. Early industrial chemistry chased cheap, reliable building blocks. Alkyl sulfonic acids—born out of the age of coal tar refinement—grabbed attention in the 30s and 40s, especially for their resilience and strong acid behavior. Eventually, the search for new reactivity pushed chemists to try out sulfonic esters as leaving groups and intermediates. Methyl ethanesulfonate, usually known under trade names like Mesylate, started making its mark in the 1960s, mostly in pharmaceutical syntheses and later in specialty polymer chemistry. Its story traveled alongside broader trends: cleaner reactions, milder conditions, and ever-tightening safety standards. Today, this compound carries its historical baggage—the good and the problematic—ever further into emerging fields.

Ethanesulfonic acid methyl ester, more commonly called methyl ethanesulfonate or MES, serves as an alkylating agent with a structure that includes a sulfonate ester linked to a methyl group. Its ability to transfer its methyl group has made it valuable in pharmaceutical, chemical, and biotechnological labs. The molecule's small size leads to decent solubility in water and many organic solvents, fitting well into different reaction setups. MES comes in clear, colorless liquid form and is sold in sealed glass or fluorinated plastic bottles to guard against hydrolysis and accidental spills, which matter a lot on the bench and in transit.

MES shows up as a faintly sweet-smelling clear liquid, with a boiling point near 146-148°C and a melting point well below room temperature. Density hovers close to 1.12 g/cm³, which means it sinks in water but disperses easily with shaking. It dissolves well in polar solvents like methanol, ethanol, and slightly less so in acetone, chloroform, or ethyl acetate—making it flexible for multi-solvent operations. Its sulfonate group stands out for chemical reactivity: electron-drawing, leaving group power, and encouraging reactions with nucleophiles. Not all users notice until a cap loosens, but it's also flammable and tends to slowly absorb water, which can spoil some precise processes.

Most chemical vendors print the standard purity of MES at 98% or higher, with water content below 0.5%. Bottles carry hazard and precaution labels in line with GHS rules: flame pictogram, exclamation mark for toxicity, and clear handling instructions. Certificates of analysis come with each batch, noting purity by GC-MS, residual acids, and sometimes heavy metals, emphasizing the importance of strict quality control especially in pharmaceutical work. It matters for the end user: repeatable results, regulatory compliance, trackable batches for recalls. Some high-purity grades target research, while technical grades might appear in industrial-scale syntheses.

Most industrial MES is made by reacting ethanesulfonyl chloride with methanol, using a base to mop up the hydrochloric acid byproduct. The trick comes in controlling moisture: water or stray alcohols can create side products that muddy yields. Larger chemical plants work under dry nitrogen or argon atmospheres, collecting the liquid product by vacuum distillation. For specialty grades used in drug development, companies also toss in purification steps—often vacuum distillation followed by activated charcoal treatments—to get rid of color and smell, crucial for downstream applications. Lab-scale protocols follow much of the same flow, with extra vigilance for side reactions.

MES reacts mainly as a methylating agent, transferring its methyl group to nucleophilic sites, especially oxygen and nitrogen atoms in organic substrates. In one lab I worked in, we relied on it for subtle methylation of amino acids, which let us create unique derivatives that were harder to reach with more brute-force reagents. It's less explosive than methyl iodide but demands respect since mistakes expose workers to genotoxic risks. Sometimes chemists tweak MES to create new sulfonate esters, or convert it into strength-matched sulfonamides by substitution at the methyl group. Its robust sulfonate backbone resists many decomposing forces, but acidic or basic conditions can eventually crack it open.

MES appears on lab shelves with names such as methyl ethanesulfonate, mesylate methyl ester, and in some old catalogs as EMS. Importantly, "MES" also refers to a common buffer but doesn't overlap structurally or functionally—mix-ups can lead to ruined experiments or worse, safety incidents. Trade names and labeling shift depending on vendor and region, but methyl ethanesulfonate stays constant across regulatory filings, material safety data sheets, and chemical catalogs. Clarity in labeling stands as a shield against accidents, especially since the compound walks the line between routine intermediate and regulated hazardous chemical.

Work with MES requires protective gloves, splash goggles, and strict waste controls. GHS classification flags it as flammable and acutely toxic, with mutagenic hazards listed in official registries like IARC and ECHA. Spills or careless handling can cause local irritation, and inhaled vapors pose systemic risks over time. Ventilated fume hoods, sealed containers, and spill kits aren’t luxuries, but baseline practice in both research and pilot plant settings. Big chemical plants use continuous monitoring, gas sensors, and emergency eye wash stations. Disposal follows hazardous waste protocols; mixtures and residues join amalgamated solvents for incineration. Training and risk communication bridge gaps between safety culture and efficiency—corners cut show up eventually, and the stakes concern more than just productivity.

MES gets a spot in pharmaceuticals, agrochemicals, fine chemical synthesis, and DNA mutagenesis studies. Small-molecule drug chemists count on MES for O-methylations of alcohols and phenols, which step into later transformations—often building complexity one functional group at a time. In agriculture, MES derivatives shape new pesticides and fungicides, tinkering properties for crop protection. In molecular biology, the reagent writes its legacy for its mutagenic effects on DNA—researchers used it to induce controlled genetic changes in microbial populations, laying groundwork for mutation screening and pathway optimization. Working with MES offers both opportunity and risk; it's not just another bottle on the shelf, but an agent that shapes outcomes for both molecules and researchers.

Ongoing R&D on MES focuses on greener synthetic routes, better downstream handling, and finding safer or more selective alternatives. Analytical chemists look for rapid, on-site tests to detect MES contamination in drug and food products, since new standards press tighter on even trace toxicants. Universities have taken up projects to explore biocompatible functionalizations using MES, trying to balance traditional reactivity with the demand for lower environmental footprint. Cross-disciplinary teams work at the frontiers: using MES in the manufacture of responsive polymers, or examining its downstream metabolites to map out long-term fate in the environment. Funding from public agencies and private industry pulls innovation in several directions—reducing exposure risk, improving shelf life, and capturing value from cleaner, more scalable syntheses.

MES’ danger sits mostly in its genotoxic potential. Animal studies show it can alkylate DNA, leading to mutations and in some cases tumor formation—a property that led to its use in genetics research but also strict workplace controls. Chronic exposure links to cancer and reproductive harm. Regulatory authorities—OSHA, REACH, and IARC among them—put strict thresholds for human contact and environmental discharge. Recent research explores biomarkers for early detection of exposure, and standard practice involves regular health monitoring for workers in high-throughput settings. Some modern alternatives, like milder methylating agents, get a closer look, but no perfect replacement matches MES’ cost-effectiveness and reactivity while dodging its health impacts so far.

Chemistry never stands still, and the next decade will reshape how MES is made, moved, and used. Process chemists chase bio-based and recyclable solvents to lower the lifecycle impact of MES production, and automation promises steadier, incident-free runs at factory scale. Regulators push for cleaner substitutes in fields like pharmaceuticals, but the mix of affordability and functional performance that MES offers holds it in the toolkit for now. Safety improvements—faster real-time detection systems, better closed-system handling, standardized operator education—aim for fewer accidents, lower casualties. Academia and industry together press for full-cycle stewardship, from raw materials to final waste, seeking sustainability without ceding power to the molecule’s chemistry. In my experience, the dual pressures of tightening legislation and scientific curiosity will push innovation, and the solutions will arrive from collaborations between chemists, engineers, and those who bear the brunt of exposure risks.

Ethanesulfonic acid methyl ester doesn’t show up in mainstream headlines or everyday conversation, but it plays a quiet, essential role in chemical laboratories and industrial processes. Scientists working in organic synthesis rely on this compound because it helps them make new molecules quickly and cleanly. Drawing from my days as a student helping with research projects, I remember hearing the lab manager call it a “reliable building block.” The phrase stuck with me, since reliable tools rarely let you down, even if they don’t grab much attention.

Chemists who study drug development often reach for ethanesulfonic acid methyl ester, particularly during what’s known as “methylation” reactions. Adding a methyl group might seem simple, but those small changes can transform the way a drug interacts with the body. For example, a molecule designed to fight bacteria can see a boost in strength and selectivity just from well-placed methyl groups. Some pharmaceutical teams use it to make antibiotics more effective or help cancer drugs bypass certain defense mechanisms in malignant cells.

The safety profile of the products made with this compound gets careful attention. In pharmaceutical industries, handling any chemical demands expertise, and mistakes easily lead to output that fails quality checks. In my own experience working with regulatory professionals, strict routines for tracking each batch and monitoring purity mean no shortcuts get taken. This oversight matters, since lives depend on the reliability of the final medicine.

Crop protection remains another major field that benefits from this compound. Some scientists use it as a stepping stone to create herbicides and pesticides that target only specific threats to crops. On many farms, farmers face the challenge of keeping pests away without poisoning soil or surrounding wildlife. Precision tools in the lab, like ethanesulfonic acid methyl ester, make possible the kind of advanced chemical products that deliver better yields with less environmental harm.

Manufacturers in the electronics industry also use it to build new materials for microchips and batteries. Creating cutting-edge phone screens or longer-lasting chargers often depends on molecules that have been collectively fine-tuned for specific tasks. For example, sulfonate groups lend stability to polymers and help control how plastics stretch and conduct electricity.

Not every application of ethanesulfonic acid methyl ester catches the public eye, but everywhere it’s used, the approach centers around minimizing waste and maximizing benefit. That has meant a shift in some labs toward greener manufacturing methods. Some teams cut down on hazardous byproducts by choosing milder reaction conditions or using advanced purification technology. I’ve met scientists who are passionate about reducing their environmental footprint and excited to discuss new purification columns that save hundreds of liters of chemicals each year.

Each field that relies on ethanesulfonic acid methyl ester faces unique challenges, but one principle crosses all boundaries: progressing with safety, precision, and care for unintended consequences. Newer processes and updates to laboratory standards keep this compound relevant, reflecting a wider trend in science toward accountability and responsible innovation.

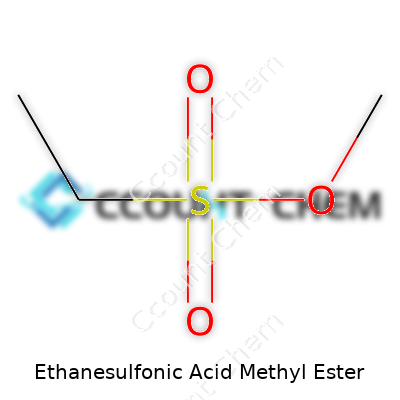

Ethanesulfonic acid methyl ester shows up in organic chemistry labs for a reason. Its formula is C3H8O3S. Dig a bit deeper, and the IUPAC name is methyl ethanesulfonate. At its core, the molecule brings together an ethane backbone, a sulfonic acid group—which interacts with other molecules in strong, compelling ways—and a methyl ester, tagged on for good measure. The actual skeletal structure looks like CH3CH2SO3CH3. Each atom has a job: the sulfur atom latches onto three oxygens and then enough carbon atoms hook things together so the molecule delivers in both stability and function.

The structure sets the tone for behavior. The ethyl group connects directly to the sulfur atom, and this sulfur links up to three oxygen atoms, as expected from the sulfonate group. The methyl group joins in through an ester bond. The result: a small but potent molecule, with a polar region willing to mix with water and a nonpolar section that stretches the molecule's uses into places where less reactive and less soluble compounds can’t go.

I’ve seen methyl ethanesulfonate get pulled off the shelf in graduate school more than once. Sometimes folks call it mesylate, and everyone knows to take care with it. The chemistry can be unforgiving: methyl ethanesulfonate works as a strong alkylating agent, which means it hands over a methyl group to nucleophiles pretty easily. That’s useful for making new carbon-sulfur bonds, or for tweaking pharmaceutical intermediates to get the right bioactivity.

This tool works in more than bench-top syntheses. In pharmaceutical research settings, you might spot it showing up as an intermediate when someone wants to test new analogs or push a lead compound into a more active or bioavailable state. The methyl ester moiety changes how the molecule handles water, how quickly it reacts, and sometimes even how well it gets into a reaction mixture without gumming up the works.

Working with methyl ethanesulfonate isn’t just about knowing the chemical structure—it means understanding what it can do to the people handling it and where it goes when finished. This compound falls into a category of alkylating agents that science flags for toxicity. Simple skin contact or inhalation can spell trouble. Literature points to genetic and cellular impacts at higher exposures. In the lab, gloves stay on, and fume hoods keep vapors away from faces.

Environmentally, methyl ethanesulfonate’s reactivity means it breaks down over time in the atmosphere and in wastewater. That’s one layer of good news, but it pays to keep stocks locked down and disposal managed as hazardous waste. If it gets into water systems undiluted, aquatic life faces serious risks.

Pushing for safer alternatives or more responsible practices forms a habit in chemistry—one I wish I saw more often early in my own career. Researchers now seek greener surrogates, rolling out less hazardous alkylating agents for some applications. Labs develop training that walks new team members through proper handling and emergency measures.

As synthetic chemists, our awareness about the molecules we use—methyl ethanesulfonate included—ties into both the science and the broader community around us. Responsible use and clear communication about hazards matter every time that bottle comes down from the shelf.

Familiar chemicals rarely make the news, but that changes fast when safety comes into question. Ethanesulfonic acid methyl ester pops up in labs, especially during organic synthesis work. Its structure looks simple and clean on paper — a sulfonic acid group connected to a methyl ester. Chemists use it for a reason: it offers unique sulfonylation possibilities in synthesis processes. The real concern builds around everyday safety and real-world exposure.

The Material Safety Data Sheet for this compound does not mince words. Skin contact can burn, and eyes risk permanent damage with enough exposure. Breathing in its vapors turns out equally tough on the respiratory system. Chemical burns from brief exposure remind anyone handling it to respect the gloves and goggles rule. This isn’t some rare, freak accident; it’s grounded in accident reports and toxicology studies, which flag corrosive effects on human tissue.

I’ve worked with similar sulfonic acid derivatives. My own protocol always took the high road: fume hood on, sleeves down, gloves checked for holes. Colleagues sometimes cut corners, which led to unnecessary burns or nasty spills. Lessons learned stick because chemical exposure isn’t just a story—it’s a sharp reminder that “minor” doesn’t always stay minor.

Plenty of acids and esters cause irritation, but ethanesulfonic acid methyl ester ramps things higher. Reports indicate severe irritation and burns from very small spills. The compound’s reactivity with water produces heat—so accidental mixing in a careless setting only magnifies danger. This makes it more aggressive than everyday lab acids like acetic acid or citric acid. Its volatility places pressure on anyone uncapping a bottle, as vapor inhalation kicks up health risks.

OSHA and NIOSH haven’t published broad-scale chronic toxicity findings for this compound. Still, acute exposure effects have been confirmed: chemical burns, severe eye damage, and possible airway inflammation. Some methyl esters, in general, raise concern because their byproducts include methanol—a known neurotoxin—but this specific ester hasn’t yet produced headline-making chronic cases. That said, plenty of cases remain unpublished or unreported, especially outside regulated workplaces.

Ignoring protocols isn’t a shortcut; it steers straight into danger. Spills cause instant burns, and residue on unprotected skin does not just sting—it can keep damaging beneath the surface. Every lab accident we read about (or experience firsthand) pushes home one lesson: respect each hazard for what it is, not what we assume it “should” be. Proper PPE—chemical goggles, face shield, gloves—shields more than just one person; it shapes safe habits for an entire team.

Working with ethanesulfonic acid methyl ester starts with training. Every researcher must know what a spill kit offers, how to ventilate properly, and why “just a few minutes” with no gloves can land someone in the hospital. Waste disposal needs careful labeling and full process adherence, so accidents after-the-fact don’t hurt custodians or waste handlers. If a lab upgrades its ventilation and runs regular safety drills, it protects more than just property; it protects well-being and future productivity.

Raising awareness about even rarely discussed chemicals matters. Clear labeling in local languages, standardized hazard signs, and company-wide reminders go a long way. Safety culture, once built, doesn’t just tick compliance boxes. It becomes the reason accidents stay rare—and preventable injury stays off the record.

Ethanesulfonic acid methyl ester isn’t something most folks have on their minds in daily life, but inside a lab or production facility, it demands real respect. You’re looking at a substance that can eat through materials, cause nasty burns, and pump out fumes that aren’t friendly to lungs or eyes. Even without years spent behind a bench, anyone who’s ever handled a bottle with a skull-and-crossbones knows the story: this isn’t just a liquid, it’s a decision point. One wrong move, and people pay the price.

Leaving bottles of volatile chemicals out in the open makes as much sense as storing gasoline next to a campfire. Ethanesulfonic acid methyl ester belongs in a corrosion-resistant, air-tight container. I used to watch colleagues tape labels half-off the side of bottles, but these labels fend off more than confusion—they stop disaster. Flooding or fumes, no one enjoys running blind through chemical chaos.

The storage area deserves careful thought. Dry, cool, shaded from sunlight. This doesn’t just cut down on leaky bottles; it calms reactions that like to speed up with heat. Moisture’s another foe. Water in the air can mess with the chemistry, break seals, or worse, set off a chain reaction. Indoor storage cabinets rated for corrosives take away a layer of risk. These cabinets hold spills, vent vapors, and give peace of mind.

I remember standing at the fume hood, nitrile gloves pulled tight, safety glasses snug, feeling the weight of the glass bottle in my hands. With compounds like methyl esters of ethanesulfonic acid, your gear isn’t a costume. Gloves keep out the burn, goggles keep vision clear, and lab coats catch those accidents most folks hope never happen.

Pouring or pipetting, you learn quickly: slow hands, sharp eyes. A drop on the bench means scrubbing with the right neutralizer, not just a wet towel. Working near fume hoods makes a big difference—I’ve felt the sting of chemical odors, and it sharpens your respect for strong ventilation. Breathing in fumes can stack up harm over the years.

Accidents punch through the calm in a hurry. Spill kits, eyewash stations, and emergency showers should stand ready, gear checked and uncluttered. People working with ethanesulfonic acid methyl ester need real drills, not just rules on a wall. I’ve watched well-trained teams mop up small spills in minutes, while a missed step or guesswork drags out a crisis.

Every time someone handles a challenging chemical safely, the lab gets a little smarter. Reviews after spills, reminders at shift change, a locker stocked with fresh gloves—these habits foster a place where people trade fear for focus. Knowledge builds over time, passed from old hands to new. Looking back, the real lesson comes from not cutting corners. Safe storage and steady handling make the difference between a good day and a headline.

Ethanesulfonic acid methyl ester doesn’t turn heads outside of research circles, but for folks who spend their days at the bench or in production, how this reagent arrives makes a real difference. I remember more than one research project slowed because the quantities on hand were too much or too little for our protocols. Ordering bulk made us worry about shelf life; small vials cost more, but we wasted less. You can see how the right package can help avoid hassle and unnecessary expense.

Labs and manufacturers aren’t locked into a single standard. Small research labs often order as little as 5 grams or 10 milliliters. Glass bottles with 10, 25, or 50 grams are common picks—easy to handle, limited exposure, less stress over chemical degradation (since this compound likes to react with moisture over time). I’ve seen startups request exactly those amounts to run pilot reactions without tying up extra cash in chemicals that might sit for months. The glass packaging stands up to acidic and ester environments better than plastic and keeps purity in check.

Bigger outfits rely on commercial-scale packaging: 100-gram, 250-gram, or half-liter containers appear on many supplier catalogs. This helps universities, contract research organizations, and chemical producers keep projects in motion without running out. Most suppliers I’ve dealt with can even bring in 1-kilogram bottles by special order, which makes sense for batch reactions, scale-ups, or process development in pharmaceuticals and fine chemicals. Bulk packaging usually translates to lower cost per unit weight, though storage and safety become much bigger challenges—regulatory rules around chemical handling tighten up quick as quantities rise.

Now, bulk drums for industrial use do exist, but they’re a specialty purchase. I’ve talked with purchasing folks in big plants who needed larger drums (5 liters, sometimes up to 25 kilograms) for continuous operations. For those jobs, suppliers often discuss custom containers—stainless steel drums or high-density polyethylene with chemical-resistant liners to control moisture and contamination. In these larger settings, on-site teams usually have the safety procedures and ventilation to handle big volumes safely.

Anyone who stores or transports chemicals such as ethanesulfonic acid methyl ester faces familiar headaches: water sensitivity, corrosiveness, and regulations. Smaller packaging cuts down on spoilage and lets users keep their inventory fresher. Some companies switched from one-kilogram containers to 250-gram bottles after calculating the throwaway cost of degraded inventory. Meanwhile, for larger operations, drum storage can shift the biggest risk to logistics and spills, so there’s a balance to strike between safety, storage capacity, and budget.

For those searching for the right option, direct communication with suppliers pays off. Many will propose custom sizes or packaging tailored to specific workflow needs—glass for lab use, coated drums for industrial scale, and so on. My own experience kept me chasing that ideal spot: enough for the next round of experiments, not so much that I shelled out for controls and disposal after a quarter on the shelf.

The size you pick sends ripples from the storeroom to the accounts office. Keeping a clear map of what you’ll use, how much you can store safely, and what your projects demand saves real money. Overbuying risks waste, but too-small packages can halt a process midstream. As always, talking to both safety officers and the finance team sheds light on which option fits everyone’s goals. In the chemistry world, the humble bottle size can be the difference between a project running smooth or coming to a grinding halt.

| Names | |

| Preferred IUPAC name | Methanesulfonic acid methyl ester |

| Other names |

Methyl ethanesulfonate Methanesulfonic acid, methyl ester Methyl sulfonic acid ethyl ester Mesylate methyl ester Ethanesulfonic acid, methyl ester |

| Pronunciation | /ˌɛθ.eɪn.sʌlˈfɒn.ɪk ˈæs.ɪd ˈmiː.θəl ˈɛs.tər/ |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | 4265-27-4 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | `/DB06724/pdb` |

| Beilstein Reference | 4074109 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:41458 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL20515 |

| ChemSpider | 73340 |

| DrugBank | DB08626 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 14b1f7f2-faad-49a1-8058-30c0b6bcb3a2 |

| EC Number | 2141-55-5 |

| Gmelin Reference | 63758 |

| KEGG | C19203 |

| MeSH | D017617 |

| PubChem CID | 60596 |

| RTECS number | KS8575000 |

| UNII | 928L1J8A58 |

| UN number | UN3277 |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | DTXSID30105931 |

| Properties | |

| Chemical formula | C3H8O3S |

| Molar mass | 110.15 g/mol |

| Appearance | Colorless liquid |

| Odor | sweet |

| Density | 1.211 g/mL at 25 °C |

| Solubility in water | soluble |

| log P | -1.0 |

| Vapor pressure | 1 mmHg (20°C) |

| Acidity (pKa) | -1.83 |

| Basicity (pKb) | -4.6 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | -8.3e-6 cm^3/mol |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.387 |

| Viscosity | 0.92 mPa·s (20 °C) |

| Dipole moment | 3.20 D |

| Thermochemistry | |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 329.6 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -374.6 kJ/mol |

| Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) | -970.7 kJ/mol |

| Hazards | |

| GHS labelling | GHS02, GHS07 |

| Pictograms | GHS05,GHS07 |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | H302, H314 |

| Precautionary statements | P210, P233, P240, P241, P242, P243, P261, P264, P271, P280, P301+P310, P303+P361+P353, P304+P340, P305+P351+P338, P312, P370+P378, P403+P235, P405, P501 |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | 2-3-1 |

| Flash point | 80 °C |

| Autoignition temperature | 240 °C |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 oral rat 650 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | LD50 (median dose): Oral rat LD50 = 226 mg/kg |

| PEL (Permissible) | Not established |

| REL (Recommended) | 10 mg |

| IDLH (Immediate danger) | Not established |

| Related compounds | |

| Related compounds |

Methanesulfonic acid Ethanesulfonic acid Ethyl methanesulfonate Methyl sulfate Methanesulfonyl chloride |