Modern biochemistry moved ahead fast in the late 20th century, and so did the demand for reliable buffer systems that could keep pH steady during experiments. The search for simpler, more predictable reagents eventually led to the discovery and development of 3-(Cyclohexylamino)-1-Propanesulfonic Acid, often called CAPS. This compound, coming into labs in the wake of Good’s buffers, offered higher stability in alkaline pH ranges and a backbone flexible enough for protein chemistry, genomics, and standard biotechnology workflows. Research journals from the 1970s and 80s documented rising use of CAPS in Western blotting and protein purification, showing how academic and industrial labs noticed its power to solve pH control problems where older buffers struggled.

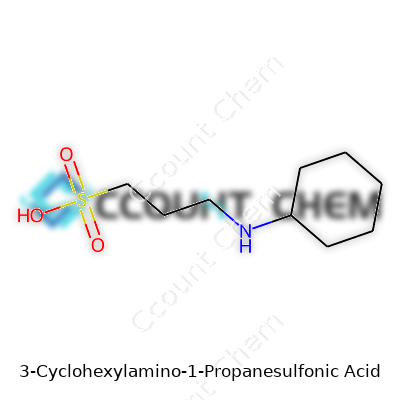

CAPS brings together several useful traits, making it popular in molecular biology and biochemistry setups. Unlike older buffers that break down or let pH drift, CAPS stands up to high pH and temperature swings. The molecule carries a sulfonic acid group and a cyclohexyl ring hooked to a propylamine bridge, so it holds onto protons more tightly over a wide pH window. Many researchers pick CAPS for protein transfer during Western blots, high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), and enzyme-linked assays, counting on its stability and low UV absorbance. CAPS keeps proteins happy, doesn’t react with many other chemicals, and avoids annoying background signals that mess with sensitive detection systems.

In its pure form, CAPS appears as a white, odorless powder, not hygroscopic, and it dissolves with relative ease in water but poorly in common organic solvents. The compound has a molecular weight of 243.33 g/mol and melts above 300°C, pointing to strong intermolecular forces and high structural stability. The sulfonic acid group gives it high water solubility, and the compound keeps a neutral charge near its pKa of about 10.4. This high pKa sets it apart from many other popular buffers, making it a favorite for biochemistry work in the alkaline range. CAPS does not degrade under normal light or gentle heat and keeps its pH control even during repetitive freezing and thawing cycles, which are common in lab life.

Manufacturers usually supply CAPS with guaranteed purity above 99% and with strict controls on heavy metals, endotoxins, and bacteria. Chemical catalogs list its full name, CAS Number 1135-40-6, molecular formula C9H19NO3S, and batch-specific data sheets. Labels include storage conditions, recommended pH ranges, and warnings about skin and eye contact, consistent with globally harmonized system (GHS) classifications. Laboratories keep records of batch origins and purity to meet requirements for research verification or regulatory audits. Certificates of Analysis (CoA) routinely track all this information for safety officers and lab managers.

Chemists usually synthesize CAPS by reacting cyclohexylamine with 1,3-propanesultone in the presence of a base under anhydrous conditions. The process yields a crude intermediate that needs purification, often by recrystallization, before final testing confirms correct identity and purity. Production runs at scale rely on careful control of temperature and exclusion of water, which prevents sultone hydrolysis, and strict filtration protocols clear out by-products. After drying, the powder gets tested by HPLC, NMR, and sometimes mass spectrometry to ensure the manufacturing process didn’t introduce impurities that could disrupt biochemical assays.

CAPS stays chemically inert in most aqueous environments but reacts under certain strong alkaline or oxidizing conditions. Standard modifications include making sodium or potassium salts, which increase solubility or adjust ionic strength for particular applications. Rarely, researchers add protective groups to tweak its behavior or fit it into custom-made resins. CAPS can work in multi-buffer systems without significant cross-reactions, so it slots into complex biochemical recipes without throwing off stoichiometry. Because it’s tough and unreactive, it survives sterilization by autoclaving or filtration, making it reliable for both bench and clinical use.

The scientific literature and product catalogs refer to CAPS in several ways: 3-(Cyclohexylamino)-1-Propanesulfonic Acid, N-Cyclohexyl-3-aminopropanesulfonic acid, and sometimes simply as CAPS Buffer. Certain suppliers also market the sodium salt form as CAPS-Na, and different research kits label it according to application—such as “Alkaline Transfer Buffer” in immunoblotting kits. Recognizing these synonyms matters when ordering or reading studies, as the same compound shows up under different names depending on the source or the translation.

Working with CAPS means following basic lab safety rules: gloves, goggles, and a lab coat at minimum. Dust can irritate lungs or eyes, though the compound doesn’t pose major toxicity risks through skin contact or minor inhalation. Users should avoid eating or drinking near the powder and keep stocks dry and tightly sealed. Waste solutions containing CAPS don’t require hazardous waste disposal in most countries, but labs following ISO or GMP standards track volumes and disposal, especially if mixed with heavy metals or solvents. Every workplace posts the relevant safety data sheet (SDS) and regular safety reviews train newcomers on handling all buffer chemicals, including CAPS.

CAPS shines in protein chemistry, especially in Western blotting and protein sequencing where confidence in pH maintenance makes or breaks results. In chemistries that need pH near 10–11—such as capillary electrophoresis, nucleic acid hybridization, and certain enzyme reactions—CAPS overtakes many old-school buffers. Analytical labs often use it in high-pH chromatography, benefiting from CAPS’ low UV absorbance at 260 nm. Some clinical and environmental labs pick CAPS in assays needing high alkaline resistance with minimal background noise, placing it on par or above TRIS and borate buffers for specialized roles.

Academic labs in biochemistry keep exploring how buffer systems mediate enzyme activity, protein folding, and antibody-antigen binding. New studies keep finding that small tweaks in buffer composition—like switching to CAPS in the alkaline zone—lead to sharper bands in Western blots or improved yields in protein purification. Companies developing diagnostic kits or recombinant proteins run trials comparing CAPS to alternative buffers, noting its ability to cut interference from contaminants or background staining. Instrument companies also tune CAPS-based solutions for precise control in automated platforms. Ongoing R&D focuses on blend formulations that add stability, extend shelf life, and broaden the operating pH range, helping CAPS stay relevant in both old and new workflows.

CAPS scores as low-toxicity in nearly all published studies. Acute oral and dermal toxicity levels rank orders of magnitude below dangerous chemicals commonly found in labs. Chronic exposure research remains limited, though so far, no reports link buffered CAPS solutions to major health problems in humans or animals. Eye or mucous membrane exposure causes brief discomfort but nothing lasting or systemic. Labs following routine protective practices avoid even these mild effects. Most toxicological interest nowadays centers on waste—whether routine disposal introduces risks to wastewater streams or aquatic systems. Preliminary reviews from regulatory bodies in North America and Europe suggest minimal environmental impact, especially at the concentrations found in most labs or industries.

Growth in protein therapeutics, genomics, and high-resolution analytical platforms keeps driving demand for buffers like CAPS. Research in bio-manufacturing seeks faster, more robust processes that can run 24/7 without tedious pH adjustments, leaning heavily on stable alkaline buffers. Chemists and engineers work on greener synthesis routes to cut waste and energy use for large-scale CAPS production, aiming to align with stricter sustainability benchmarks. With big jumps in cell-free synthetic biology, and digital PCR, the need for low-interference, temperature-stable buffers only rises. In the next decade, advances in automation, nanobiotechnology, and personalized diagnostics will push CAPS into hundreds of new protocols, so long as the chemistry community keeps building on its strengths for precision, safety, and reliability.

3-(Cyclohexylamino)-1-Propanesulfonic Acid, better known as CAPS, pops up in a lot of labs, especially those focused on biology and chemistry. If you’ve done protein research or tinkered in a biochemistry lab, you've probably worked with CAPS. The reason is straightforward: scientists need a stable environment for their molecules, so they use buffers to keep things steady. CAPS handles this job well, especially when you’re working with slightly alkaline solutions. Its pH buffering range, sitting around 9.7 to 11.1, gives it an advantage for experiments that don’t play nice in the usual neutral or acidic environments.

Protein work is finicky. Proteins fold and unfold easily, get sticky, or lose their shape without the right surroundings. During experiments—particularly electrophoresis, where researchers separate proteins based on their size or charge—a buffer like CAPS makes sure the pH stays nearly the same, so proteins don’t fall apart. CAPS doesn’t mess with proteins much, making it a favorite choice. Plus, it doesn't interfere with UV readings, so it doesn’t cloud results when researchers measure proteins in a solution. For anyone working on purifying enzymes or mapping the steps of a metabolic process, using CAPS keeps things predictable and dependable.

Finding the right buffer isn’t just about picking what’s on the shelf. Chemicals behave differently across temperature, salt content, and the kind of molecules in the mix. CAPS stands out for its stability at higher pH and its low ability to interact with delicate proteins or dyes. For example, TRIS works well for many tasks but can react with certain chemicals. CAPS usually stays out of the way, which adds to its appeal when experiments demand clean, consistent outcomes. Avoiding interference is crucial, as small changes can lead to wrong conclusions, wasted samples, or inaccurate measurements. As someone who’s watched gels run in electrophoresis, I’ve seen how picking the right buffer keeps bands clear and sharp instead of fuzzy and hard to interpret.

Staining proteins after they’ve moved through an electrophoresis gel is a key part of documenting results. CAPS supports the development of stains like nitroblue tetrazolium, which makes specific proteins show up more clearly. In diagnostics, such as lab kits for measuring enzyme levels, CAPS helps by maintaining the exact pH needed for test accuracy. Even in molecular biology, certain DNA sequencing reactions run better with CAPS, since it doesn’t mess with enzymes or fluorescent tags. Good results in these areas often come down to having a buffer that’s stable, neutral, and unwavering under harsh conditions.

CAPS isn’t foolproof. It absorbs carbon dioxide from the air, leading to unwanted pH shifts if left uncovered. Storing solutions in tight, sealed containers goes a long way toward stretching shelf life. Researchers also keep documentation handy so they know exactly how CAPS interacts with other chemicals in the system. Consistent practices like labeling and frequent pH checks cut down on surprises during experiments. Sharing tips and experience within a research group helps everyone avoid common pitfalls. My own work benefited from careful recordkeeping, and it still pays off in fewer mistakes and more reliable data.

Chemistry might sound complicated, but it boils down to building blocks and relationships. Take 3-(Cyclohexylamino)-1-propanesulfonic acid, better known in labs as CAPS. This compound isn't just a string of syllables—it fills a real need in science. CAPS works as a buffering agent, keeping pH steady during experiments that need reliable results. Fluctuating pH can send data off track, and researchers trust compounds like this to offer control in their experiments. With a formula of C9H19NO3S, each atom does its part. Nine carbons form the backbone with a cyclohexyl ring, while the sulfonic acid group controls acidity.

The molecular weight sits at 221.32 grams per mole. That number matters every time someone in a lab grabs the bottle and measures out a sample. Dose calculation turns into a simple matter: how much does a mole weigh, and how much do you need to add? Skipping this step can mean wasted chemicals, lost time, or corrupted results. The process gets more important in drug development, where consistency and accuracy drive progress and keep people safe.

Every time I set foot in the lab, I come back to basics—what's in the bottle, and how pure is it? The chemical formula isn't just words on a label. Seeing C9H19NO3S tells me I'm handling a molecule with a cyclohexyl ring joined to an amino group and a three-carbon chain, ending in a sulfonic acid. That structure makes it ideal for buffering in systems where regular buffers won’t cut it, like electrophoresis or protein purification using certain pH zones. More traditional buffers stop working when things heat up or cool down, but CAPS holds up across temperature swings and high ionic strengths.

Research needs dependability. The wrong buffer or a misread label leads to untrustworthy data. People spend countless hours running controls to make sure their system behaves as expected. With a known compound like 3-(Cyclohexylamino)-1-propanesulfonic acid, researchers feel more confident in going after tough questions. Some buffers break down at high temperatures or leach out unwanted ions; this molecule stands up to more rigorous settings, reducing interference during delicate processes such as enzyme assays.

Exploring safer handling and greener syntheses has become more important. Older manufacturing routes often relied on solvents that harm the environment. Moving forward, modern labs work towards cleaner methods, using less water and creating fewer byproducts. Training lab workers to measure, handle, and dispose of these chemicals safely protects people and ecosystems. Labeling, correct storage, and waste management remain critical steps in the daily routine.

Education can help avoid accidental mixes or waste. Workshops, digital guides, and clear safety sheets offer stepwise instructions for new researchers. Sharing knowledge about why C9H19NO3S behaves as it does—its acid dissociation constant, comfort range for pH, and common compatibility—makes the job less intimidating.

Whether you measure milligrams or mix up a liter batch, knowing both molecular structure and weight makes a difference in every outcome. Good science grows from understanding both theory and practice, down to every atom.

Working with chemicals sharpens your respect for order. Not just because you aim for clean results, but because it protects everyone in the building. 3-(Cyclohexylamino)-1-Propanesulfonic acid, or CAPS as you might see on the bottle, looks pretty tame on paper, but the reasons for good storage reach beyond how a powder appears. Anyone who’s dealt with a corroded label or mystery residue on a forgotten shelf knows that taking shortcuts only brings headaches later.

Experience teaches you to watch out for the three enemies of chemical stability. CAPS starts to break down under damp conditions, and the sulfonic acid group can pull water right out of the air. Get enough moisture in there and you’re not only inviting clumps but changing how the compound behaves in your experiments. Keep it in a tight-sealing bottle, never just stuck back in its original shipping bag. Toss a new silica gel desiccant in there, even if the lab supervisor rolls his eyes at “extra steps.”

Harsh light plus chemistry shelf equals slow disaster, especially for chemicals that don’t take kindly to UV. CAPS holds up best without bright bench lights or sunlight beaming through the lab window. Store the container tucked in a cabinet, and shy away from glass jars if there’s any risk the compound will see hours of daylight.

Don’t forget temperature swings. CAPS doesn’t need a deep freeze, but long storage up near the ceiling where summer hits hardest shortens its useful life. Aim for cool and steady, the same as you’d want for your favorite spice in the kitchen. For most labs, this means a dedicated chemical storage fridge set between 2–8°C, not a back corner that bakes in the afternoon.

Once, I watched a new tech pour half a gram of the “white stuff” into solution, only to ruin a full day’s work. Turns out, the unlabeled bottle wasn’t what anyone thought. Proper labeling solves more problems than fancy storage gear ever could. Write the date, chemical name, concentration if it’s a solution, and keep logs updated. Everyone working on the bench after you, including yourself, avoids mistakes that way.

Take inventory once a month. I ignored the advice as a student, but now I see how much money and time it saves. You catch container leaks or signs of degradation—yellowing powder, strange clumps—before it ruins test results or eats a hole in your shelf.

Many people skim past Safety Data Sheets (SDS), but information buried inside tells you a lot about storage. The sheet for CAPS notes stability in dry, cool places and says to steer clear of incompatible materials. Don’t toss acids and bases together on the same shelf. Keep CAPS far from oxidizers and always off the floor. Lower shelving means fewer accidents if a bottle slips and falls.

Good habits stick around. If one person in a lab treats storage as a no-big-deal task, it spreads. The opposite applies, too. Details like a tightly closed cap, a dated label, and picking the right shelf build trust in the results, help the whole team, and make each experiment count. That kind of care keeps labs safe and lets science move forward, bottle by bottle.

Sitting on the shelf, 3-(Cyclohexylamino)-1-Propanesulfonic Acid—usually called CAPS buffer in the lab—doesn’t look much different from the other jars filled with industry-standard buffer powders. These chemical containers don’t scream danger with bright warning labels. Still, working around this and similar chemicals day after day, I’ve learned not to assume safety based on a friendly common name or an innocent appearance.

Let’s look straight at the data. The Material Safety Data Sheet (MSDS) for CAPS doesn’t call it highly toxic, flammable, or corrosive. You won’t see the bright red pictograms shouting about acute toxicity. It does note the possibility of irritation if you get the powder or a concentrated solution on skin or in eyes. Breathing a lot of the dust can leave you coughing or sneezing. Swallowing a mouthful won’t send you to the ER, but you could face nausea or stomach discomfort. That’s pretty common fare for organic sulfonic acids. It won’t melt through your gloves or destroy your lab coat. Still, stories about complacent grad students spending hours scrubbing their itchy hands after careless handling remind me why that safe isn’t quite as straightforward as the paperwork suggests.

Every scientist who has scooped powder out of bulk bottles with a spatula knows the truth: dust floats, it lands where you least expect, and someone always forgets their gloves in the rush to finish up before coffee break. CAPS won’t cause a chemical burn or create deadly fumes, but simple slips add up. Accidental contact with skin, eyes, or airways happens easily. No, it’s not a panic moment, but ignoring goggles, gloves, or good hand washing leads to persistent irritations and a culture of shortcuts. Last year, I noticed two interns weighing buffers with bare hands, trying to move quickly after a deadline reminder popped up. That dust had set off sneezing fits in the lab all morning—a simple problem traced back to forgotten masks and a rush to cut corners.

No alarming restrictions target CAPS under OSHA or REACH. Disposal doesn’t require a full hazmat team, so it lands in the “moderate caution” category for most institutions. From an environmental angle, standard wastewater treatment handles small, dilute amounts. Tossing out large quantities or repeated dumping, though, puts strain on any system. Companies serious about responsible science don’t use the bare minimum rules as an excuse, and neither should universities. Our lab moved to a closed-waste system for all buffer solutions, not because we had to, but because the best-run labs don’t leave anything to luck or chance.

Real safety starts with a culture of care, not compliance. Every trainer will say goggles and gloves, but the experienced scientist notices the shortcuts before they become routine. Use the chemical fume hood—even if the acid isn’t volatile. Clean up powder spills completely, no matter how minor. Store all open buffers in a designated dry area, and label everything, since powdered acids can look alike after a spill or cross-contamination. Training new team members and sharing personal stories about the “minor” incidents, like unexpected coughs or rashes, brings the message home better than any regulation.

3-(Cyclohexylamino)-1-Propanesulfonic Acid doesn’t demand special permits, but a thoughtful approach to handling, disposal, and everyday discipline keeps both people and research safer. Common sense, real stories, and strong team habits do more than the thickest binder full of generic safety rules. My own missteps taught me that lesson faster than any checklist ever could.

Walking into a typical research lab, shelves hold all sorts of chemicals, but for many of us, 3-(Cyclohexylamino)-1-Propanesulfonic Acid, usually called CAPS, stands out because it handles a pH range that stubborn buffers like Tris and HEPES simply can’t touch. Anyone who’s run a protein electrophoresis using alkaline conditions probably has a memory or two about how tough it is to keep everything stable above pH 10. CAPS covers ground between pH 9.7 and 11.1, giving experiments in DNA blotting, protein transfer, and enzyme reactions a reliable backbone where fewer alternatives exist.

In most practical lab work, the concentration sweet spot for CAPS falls between 10 mM and 100 mM. Often I see protocols call for 50 mM, and I’ve followed that guidance myself to get clear, repeatable results. Go below 10 mM and the buffer’s ability to resist pH shifts drops fast. That fragile buffer lets tiny introductions of acid or base throw your experiment off track.

Above 100 mM, problems can sneak up. High concentrations raise ionic strength beyond what’s needed, nudging proteins to behave differently. Once, I ran an alkaline western blot using 200 mM CAPS by mistake. The gel ran slower, the transfer took longer, and proteins looked blurred instead of sharp. That experience taught me how ionic strength from the buffer itself influences the migration and separation of macromolecules—a fact not always obvious from textbook charts but painfully clear on ruined blots.

CAPS has a pKa around 10.4 at room temperature—data anyone can check in Sigma data sheets or the original Good’s buffer publications. Reliable manufacturers recommend concentrations that don’t let the pH fluctuate every time a reagent’s added. At 50 mM, the buffer handles pH jumps while adding sample or reagents. It also keeps osmotic pressure under control, which matters if working with cells or sensitive enzymes that quit at a hint of osmotic shock.

Labs using CAPS for transfer in protein work, such as western blots, usually rely on 10 to 50 mM concentrations. Published protocols from manufacturers like Bio-Rad list these figures, and in my own work, going over 100 mM rarely brings added benefit. Instead, it burns through valuable chemical only to make the solution saltier than the samples need—a waste and a headache.

One simple solution: mix only as much buffer as you need. Over time, CAPS solutions can soak up CO2 from the air, throwing off pH. Keeping buffer covered and fresh holds pH steady. For high-precision work, double-check pH at working temperature, not just at room temperature. Some lab meters drift, and even a fraction of a unit matters when working near the pKa.

Another tip: pair CAPS with ultra-pure water. Regular tap water, or even old distilled water, often drags down pH accuracy. Filters and deionizers help—more so at the low end of the recommended range. Staying within that 10 to 100 mM bracket, using freshly prepared solutions, and verifying pH repeatedly safeguards the data from silent shifts that ruin replicability and trust in the results.

Experience proves the 10–100 mM range isn’t just about technical accuracy—it’s about workability. This window keeps experiments possible, affordable, and reliable whether troubleshooting protein transfer, enzyme reactions, or analytical chemistry. When results matter, sticking to this concentration range helps every ml count for more.

| Names | |

| Preferred IUPAC name | 3-(Cyclohexylaminyl)propane-1-sulfonic acid |

| Other names |

CAPS Cyclohexylaminopropanesulfonic acid |

| Pronunciation | /ˈsaɪ.kloʊˌhɛk.sɪl.əˌmiː.noʊ.prəˈpeɪn.sʌlˌfə.nɪk ˈæs.ɪd/ |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | 1135-40-6 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | `3D model (JSmol)`: `CC(CS(=O)(=O)O)NCC1CCCCC1` |

| Beilstein Reference | 76190 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:39050 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL113483 |

| ChemSpider | 81509 |

| DrugBank | DB01942 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 03f265af-fd6b-4077-b9fa-4fd43a5f3b77 |

| EC Number | 68399-77-9 |

| Gmelin Reference | 88222 |

| KEGG | C00859 |

| MeSH | D020555 |

| PubChem CID | 103364 |

| RTECS number | TC8750000 |

| UNII | Z9CXT5Q7PT |

| UN number | UN3335 |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | DTXSID8035069 |

| Properties | |

| Chemical formula | C9H19NO3S |

| Molar mass | 221.32 g/mol |

| Appearance | White crystalline powder |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | 1.108 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | freely soluble |

| log P | -2.3 |

| Acidity (pKa) | 9.7 |

| Basicity (pKb) | 9.4 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | -54.36·10⁻⁶ cm³/mol |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.528 |

| Dipole moment | 6.49 D |

| Thermochemistry | |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 324.6 J/mol·K |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -552.8 kJ/mol |

| Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) | -1685 kJ·mol⁻¹ |

| Pharmacology | |

| ATC code | B05CX09 |

| Hazards | |

| Main hazards | May cause respiratory irritation. Causes serious eye irritation. Causes skin irritation. |

| GHS labelling | GHS07, GHS08 |

| Pictograms | GHS07 |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | H302, H315, H319, H335 |

| Precautionary statements | Precautionary statements: P261, P264, P271, P272, P280, P302+P352, P305+P351+P338, P362+P364, P501 |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | 1-1-0 |

| Flash point | > 108 °C |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 Oral Rat 5,000 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | LD50 (median dose): >5 gm/kg (rat, oral) |

| NIOSH | SY8175000 |

| REL (Recommended) | 100 mg/m³ |

| Related compounds | |

| Related compounds |

CHES CAPSO CAPS MES ACES TES |