Interest in 3,3,4,4,5,5,6,6,7,7,8,8,8-tridecafluorooctanesulphonic acid began picking up in the mid-20th century as the chemical industry was booming and chemists looked for fluorinated compounds that could withstand corrosive forces and surfactant demand. Many of these compounds started out in military and performance coatings before the public started using them in more products, such as water-repellent coatings, nonstick cookware, and firefighting foams. Early work came out of curiosity, frankly, and out of a desire to solve stubborn problems in repelling oil and water from surfaces. As research continued, scientists realized these chemicals tended to linger in the environment and in human bodies. At first, people didn’t understand the impact long-term exposure would have on health or ecology.

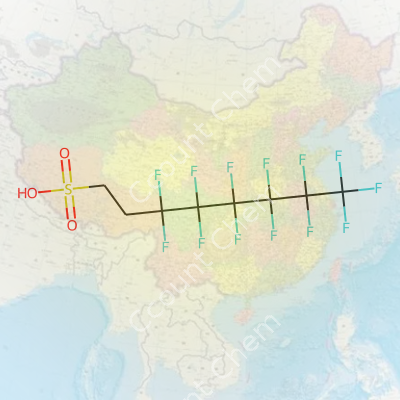

What defines this compound is its long, fluorinated carbon chain attached to a sulfonic acid group. This structure helps it act as a supercharged surfactant: any place you need something to resist water or grease, this acid shows up in the conversation. Its chemical persistence means it resists breaking down under sunlight, intense acids, or bases. A lot of specialty applications arose from those unique strengths—for example, in the plating and electronics industries, or as an essential ingredient in industrial cleaning agents. Over time, regulatory scrutiny and consumer questions began to pressure manufacturers to rethink production and disposal. The product’s journey from innovation to controversy underscores how industries change with better knowledge about their tools.

The compound appears as a white or off-white solid, sometimes sold as a powder, sometimes in solution. Fluorinated chains bring both slick, almost oily texture, and a knack for pushing grease and water away, which made these materials popular for repelling stains. The carbon-fluorine bond stands out for its durability, resisting heat, acids, bases, and nearly everything else. While soluble in water and polar solvents, the acid head groups provide a measurable level of ionic mobility, which explains how they end up traveling far in groundwater systems. This stability and mobility both act as double-edged swords: powerful for commerce, stubborn for regulation and cleanup.

Manufacturers typically supply these chemicals at high purity, often above 98%. Labels indicate molecular formula (C8F13SO3H), appearance, water solubility, melting point (usually above 180°C), and relevant hazard statements. The labeling includes guidance on storage—cool, dry places—and recommends using personal protective equipment. Material safety data sheets spell out handling, exposure limits, and first-aid directions. Technical data don’t just cater to labs; users in industrial settings need every bit of detail because misuse can trigger health or environmental trouble. Facilities often require barcoding or tracking for inventory control, which reduces chances for accidental release.

Making this acid is a feat of synthetic endurance. The process begins with octanes, then fluorinated under pressure using electrochemical fluorination or telomerization in the presence of a sulfonic acid precursor. Skilled chemists must carefully separate the desired chain length from a mix of byproducts, then purify and convert it into the desired acid. Yield efficiency often takes a hit due to tough separation steps, but the industry refined these steps to squeeze out every bit of useful material. Industrial-scale reactions require careful control of temperature and pressure to prevent mishaps. Equipment for these steps generally includes acid-resistant linings and scrupulous leak controls.

On its own, 3,3,4,4,5,5,6,6,7,7,8,8,8-tridecafluorooctanesulphonic acid is remarkably unreactive, which makes modification tricky. Sulfonic acids serve as strong acids, able to donate protons and form a wide range of salts. Chemists can turn the acid into its potassium or sodium salt for easier handling, or into reactive esters for use in performance polymers. Direct reactions with reducing agents or powerful nucleophiles tend to fail or create messy byproducts, so most modifications work by transforming the head group, not the tail. Efficient industrial use sometimes calls for small tweaks in formulation to fit specific processes—adjusting pH, blending with compatible solvents, or neutralizing the acid.

The full IUPAC name often gives way to shorter tags: tridecafluorooctanesulfonic acid, TDFOSA, and sometimes just perfluorooctanesulphonic acid (abbreviated PFOS, though different chain lengths exist under the PFOS umbrella). In catalogs, companies sell it as an analytical standard or as part of a specialized mixture, each with its own catalog number and safety instructions. Trademarked versions sometimes circulate, especially for proprietary blends or stabilized forms. Despite the variety, most professionals learn to double-check structures, since confusion with close relatives like perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) can affect data and safety compliance.

Handling the acid means treating it with respect. Even small spills present a cleanup challenge, since these compounds do not break down with routine detergents or simple dilution. Professional guidelines usually require gloves, goggles, and proper fume hoods, with strict prohibition on draining into sewers or general waste. Many countries impose exposure limits for workers and require regular blood tests to check for buildup. The U.S. EPA, European Chemicals Agency, and other authorities treat these fluorinated acids as potential substances of very high concern. Strict labeling, tracking, and specialized disposal facilities reflect a worldwide effort to minimize risk—nobody wants to repeat the mistakes of mass contamination seen in past decades.

Decades ago, products containing tridecafluorooctanesulphonic acid found their way into chrome plating, electrochemical cells, semiconductors, and firefighting foams. The chemical’s ability to form thin, resilient layers kept metals from corroding and stopped fires from reigniting in life-or-death moments. Textile treatments and carpet manufacturers leaned on its water and stain repelling action. Legal action and public scrutiny reluctantly pushed companies to seek out safer replacements. Today, survey work and remediation often focus on dismantling or treating legacies from older equipment, while regulated use sticks to tightly controlled settings. Consumer products largely shifted to alternative chemistries, although legacy contamination lingers.

Scientists pour energy into both detection and remediation techniques. Analytical chemists push detection limits lower, piecing together exact levels in human blood, fish tissue, and soil. Environmental engineers work on novel absorbents, using activated carbon or specialized polymers to filter contaminated water. Chemists in green chemistry look for biodegradable surfactants that can take on the same industrial roles without sticking around for centuries. Efforts also stretch into epidemiology: collecting data on rates of certain cancers, thyroid disruptions, and immune disorders in affected communities. Robust data collection, transparent standards, and collaboration across borders shape the present direction of research—a global team effort in both tech and policy.

Early on, people underestimated exposure risks, partly because workers didn’t show immediate symptoms. Over decades, blood levels of PFOS and related acids climbed in both people and wildlife, prompting closer scrutiny. Researchers linked exposure to liver and immune system damage, developmental delays, thyroid issues, and heightened cancer risk, particularly for folks near production sites. Lab studies on rats and monkeys confirmed long biological half-lives, anywhere from five years in humans, far longer than most other industrial solvents or surfactants. Continuous monitoring of workers and community members prompted sweeping restrictions and phase-outs, an approach that continues as new evidence emerges almost every year.

The era of widespread, barely regulated use of tridecafluorooctanesulphonic acid is clearly winding down. International agreements such as the Stockholm Convention urge signatories to eliminate or strictly control articles containing this acid. More countries ramp up bans as detection methods uncover legacy contamination in drinking water, food, and wildlife. Yet total phaseout remains complicated: industrial users struggle to find replacements with similar thermal and chemical endurance. New molecules come into the spotlight, boasting shorter chains and better breakdown rates, but even these face tough scrutiny. A practical path forward calls for open collaboration across industry, public health, and environmental scientists. Cleanup operations, new manufacturing controls, and research into harm reduction will likely keep this acid in the headlines, reminding everyone why strong oversight and constant vigilance matter wherever chemicals might outlast the applications they served.

In labs and industrial sites, people throw around complicated names for chemicals all the time. One of those tongue-twisters is 3,3,4,4,5,5,6,6,7,7,8,8,8-Tridecafluorooctanesulphonic acid, a strong acid loaded with fluorine atoms. Folks familiar with chemical manufacturing know this compound by its shorter nickname—TDFA. It falls under the broader umbrella of perfluorinated substances, sharing some traits with notorious cousins like PFOS and PFOA.

Factories with a need for intense chemical resilience make use of Tridecafluorooctanesulphonic acid pretty often. Surfaces treated with TDFA gain non-stick, stain-resistant, and water-repellent powers. It gets into firefighting foams, too. Firefighters count on its ability to smother liquid fuel fires. The aviation industry once relied heavily on foams containing these types of chemicals around runways and hangars. Textile mills soaked carpets and fabrics in solutions containing TDFA. Electronics makers love the stuff because of its heat and chemical resistance. Printed circuit boards come cleaner, and microchips form under more reliable conditions thanks to perfluorinated acids.

There’s convenience and power in a molecule like TDFA. Modern technology and emergency services both owe some of their success to these chemicals. But that usefulness creates headaches. Research points out how persistent these compounds stay in water, soil, and even our blood. Scientists label TDFA as a “forever chemical.” It won’t break down for decades, if not centuries. Reports out of Europe and North America show traces of it slipping into local water supplies. Warnings flag up in food chains, where it lands on dinner tables—moving from rivers and lakes into fish, then up the food web.

Years back, people didn’t think much about what happened to these acids once they left the factory gates. Now, doctors see a pattern. Studies from the US and the EU link exposure to increased cholesterol, immune issues, and even certain cancers. Farm animals drinking water contaminated by fluorinated compounds face stunted growth. Communities living downstream from manufacturing hubs launch lawsuits and demand answers.

Nobody can pretend the genie goes back in the bottle. The industries that use TDFA now look for safer replacements. Some chemical engineers argue for “shorter-chain” alternatives—these break down easier and clear from the body faster. Others back new cleaning and surfactant technologies at the design stage to limit reliance on forever chemicals. Still, real change comes from oversight and tough regulation. Europe’s REACH protocols demand makers prove safety before selling. The US EPA tightens the screws with stricter water standards.

Cleanup poses its own challenge. Some companies test activated carbon filters to catch perfluorinated compounds in water. Others turn to high-heat destruction or plasma-based treatment. Truth is, progress moves slowly, as developers try to match TDFA’s performance without repeating the same mistakes.

It’s easy to appreciate how crucial 3,3,4,4,5,5,6,6,7,7,8,8,8-Tridecafluorooctanesulphonic acid once seemed for modern living. Those benefits now come with a real price tag for health and the planet. Communities, health experts, and manufacturers seek a future built on better choices—ones that don’t cling to the environment or to us long after their job is done.

3,3,4,4,5,5,6,6,7,7,8,8,8-Tridecafluorooctanesulphonic acid, more familiar to environmental scientists as a PFAS compound, carries a heavy load of health concerns. PFAS have made their way into everyday products: waterproof jackets, food wrappers, fire-fighting foams. I remember doing a household cupboard cleanout and spotting these long words on product labels. At the time, nobody told me these substances stick around almost forever, both in the environment and inside us.

People rely on water and food safety. Researchers worldwide have chased PFAS across rivers, soil, fish, and even human blood. The facts keep piling up: this family of chemicals, including tridecafluorooctanesulphonic acid, resists breaking down. The human body doesn't know how to get rid of them quickly. Once inside, they can build up over time.

Epidemiologists studied groups exposed to PFAS in workplaces and communities. Their findings highlight risks related to cholesterol changes, impacts on the immune system, and potential links to some cancers. I followed a story out of Michigan a couple of years ago, where drinking water contamination put a spotlight on these compounds. Local kids walked around with test results showing traces in their blood, and everyone started questioning what role these chemicals play in rising health issues.

Day-to-day exposure often comes quietly. Stuff like microwave popcorn bags, stain-resistant carpets, and cleaning sprays can contain PFAS. Over time, even low levels add up. In one study, more than 95% of Americans had PFAS traces in their bodies. There’s a reason scientists call them “forever chemicals.”

Dog owners sometimes worry about contaminated parks and streams. Parents wonder what’s in the non-stick pans and plastic containers at home. This uncertainty chips away at trust in consumer products.

The problem doesn’t fix itself. Some states and countries are banning older PFAS outright. Water utilities invest in treatment systems like activated carbon and reverse osmosis, though these upgrades cost millions. The EPA set new limits for PFAS in drinking water in 2024, aiming to reduce risks, but the rollout remains tough for rural communities facing outdated infrastructure.

Companies experiment with alternative materials, but shoppers have little way of knowing what replaced the old formulas. Clear labeling, strong enforcement, and real penalties for polluters matter. Neighborhood groups in affected areas push for faster cleanup and better transparency, often facing slow-moving bureaucracy. Real progress takes more than policy—it calls for widespread testing, health monitoring, and meaningful support for those already affected.

People have the right to know about the risks hiding in their goods and water. Real health protection comes from a mix of smart research, tough regulations, and demanding answers from industry. In my own experience, nothing gets fixed until the public gets involved—speaking up at town halls, writing lawmakers, and keeping steady pressure until change finally comes.

Science keeps building the case: tridecafluorooctanesulphonic acid shouldn’t circulate unnoticed in households, bodies, or the wider world. Action, not just awareness, will start to turn the tide.

Every time I walk into a chemical storage space, I find myself thinking about the long game. Some chemicals sting—others last forever in the soil or creep through groundwater over decades. 3,3,4,4,5,5,6,6,7,7,8,8,8-Tridecafluorooctanesulphonic acid (abbreviated as FOSAA, sometimes also PFOSAA) stands as a good example of the latter. Its stable structure lets it resist breaking down, and that’s where storage choices take on real weight. News keeps surfacing about PFAS chemicals, highlighting how they build up in the environment and living things. After years in environmental science, caution grows into a habit. This substance’s strong tendency to stay put—on surfaces, in soil—signals the need for extra vigilance.

I’ve helped design storage plans in industrial and research settings. With FOSAA, I trust nothing less than tight secondary containment inside clearly marked, corrosion-resistant vessels. HDPE (high-density polyethylene) or fluoropolymer containers resist the acid’s stubborn chemistry better than most metals or glass. Keeping such a chemical in mild steel, for instance, will likely lead to leaks or reactions. Leaks often go unnoticed until it’s too late and cleanup is a regulatory and public relations disaster.

Temperature matters here, too. FOSAA doesn’t combust easily but high heat degrades packaging and risks secondary reactions. A climate-controlled and ventilated area works best. This isn’t a material to tuck away in a corner next to the mop closet or lunchroom. Technicians accustomed to traditional acids and bases quickly learn PFAS substances defy expectations. Spill trays—solid, chemical-resistant ones—catch drips, and regularly checked labels prevent mixups after routine shifts or staff turnover.

Environmental Health and Safety audits used to make me nervous, until one incident drove home their purpose. We found an unmarked jug—nobody could say if it was six weeks or six years old, or who last touched it. Incidents like that play out at companies big and small, risking real harm to workers and the local water supply. Clear records matter, not because regulators want paperwork, but because people and the environment deserve protection. Outdated stockpiles also tempt companies to cut corners—disposal gets expensive fast. Organized, documented storage stops problems from accumulating in the shadows.

Lined drums with secure closures don’t cost much compared to environmental lawsuits. Color-coded storage areas and frequent training for staff close the gap between policy and daily reality. Years of seeing the long-term effects of lax practices shape my approach: prompt labeling, regular inspections, attention to changing guidelines about what’s considered “safe.” With global conversations now focused on PFAS cleanup, the risks of inching outside best practices have never been clearer. Integrity with hazardous materials starts long before they reach a waste contractor’s truck.

Proper storage of persistent chemicals isn’t a private matter—it’s a social contract. Water utilities and farmers worry about invisible contamination, and that burden shouldn’t fall solely on the next generation. Fact-based storage practices, rooted in respect for the science and taught through hands-on experience, keep workplaces safer and communities healthier.

Walk past a factory tucked behind fences or scan the label on old firefighting foam, and this unwieldy name—3,3,4,4,5,5,6,6,7,7,8,8,8-Tridecafluorooctanesulphonic Acid—might never show up. Still, folks working in wastewater, environmental health, or chemical labs know it as one of the "forever chemicals." This doesn’t disappear after one season or even a few decades.

Scientists have dug into these chemicals, called perfluoroalkyl substances, because they just don’t break down. Tridecafluorooctanesulphonic acid hangs tight in soil, water, and living things for years. Rivers run with the same molecules that left an industrial pipe long before. The build-up keeps health officials up at night, since this stuff gets into fish, drinking water, and even people’s blood.

I remember a conference where a researcher pointed to a global map with broad red bands—places where these chemicals had traveled thousands of miles, following the water and the wind. You don't need a PhD to see that what gets flushed downstream comes back to us one way or another. According to the US Environmental Protection Agency, blood tests show nearly everyone carries trace levels of these chemicals today.

This molecule’s super-strong carbon-fluorine bonds don’t give up easily. Great for making stains vanish from carpets and keeping foam from collapsing in extreme heat. Bad for letting life move forward in a way that keeps lakes drinkable or food chains healthy. In studies, fish exposed in contaminated streams lose their ability to thrive, and birds that eat them pass those problems on to their offspring. Farmers and anglers in some areas now avoid their own land or harvest because water picks up factory runoff too dangerous for the dinner table.

The world has seen this script before with leaded gasoline and asbestos—the chemicals seem unbeatable until the price of using them stacks higher than imagined. Tridecafluorooctanesulphonic acid follows that pattern. The European Food Safety Authority has linked similar substances to concerns over liver damage, cholesterol issues, even changes in children’s immune systems.

Shifting from blame to solutions starts with cutting the flow at the source. Countries have chipped away at uses of related perfluorinated compounds. In my town, activists pushed fire departments to buy foams without these ingredients after testing showed high levels in local streams. This pressure works best when manufacturers step up with safer substitutes that don’t stick around forever.

Cleaning up what’s already out there doesn’t come easy; traditional filters struggle to grab these slippery molecules. High-temperature incineration and advanced chemical treatments promise better results, but they bring expense and risk. Some scientists are experimenting with specialized bacteria or clever filters based on activated carbon or ion exchange. These methods work in pilot sites, though scaling up remains a constant battle.

Regulations help draw a line by forcing polluters to clean up and limit new releases. Community science projects have filled gaps, too: people test their own water and bring back data to local governments. I’ve seen that kind of bottom-up pressure drive real action, even in stubborn bureaucracies.

No simple fix wipes away the risk of tridecafluorooctanesulphonic acid, but focus on this issue keeps growing. Every time a law passes or research turns up new ways to filter water, it chips away at a chemical legacy laid down over generations. By sharing information, demanding transparency, and pushing for safer technologies, people can start to turn a tide that once seemed impossible to move.

3,3,4,4,5,5,6,6,7,7,8,8,8-Tridecafluorooctanesulphonic acid—often called a PFAS—lands on radars because it turns up where we least want it. Stain-resistant carpets, fire-fighting foams, non-stick cookware: this chemical does its job in consumer products, but it sticks around for years in water, soil, and the human body. Some communities wrestle with contaminated drinking water and rising health at risk as a result.

Bans and restrictions for long-chain PFAS aren’t equal in every country. The European Union puts up strict rules under REACH. The U.S. follows a slower path. Right now, the Environmental Protection Agency treats PFAS as an “emerging contaminant.” Certain states—Michigan, California, New Jersey—take stronger steps than federal policymakers. For a chemical that can move across borders through air and water, this patchwork regulation creates blind spots. Residents living near factories or firefighting training sites often learn about contamination only after years of exposure.

Many regulators point to the enormous family of PFAS, over 4,700 variations, and the way some replacements swap one risky cousin for another. Outright banning gets tricky—big manufacturers have lots at stake, and alternative materials can cost more or work less reliably in the short term. Not every country has the resources to monitor water and test for obscure chemicals, especially when labs need specialized equipment.

Scientific studies and reports from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, along with work by research bodies across the world, link PFAS exposure to increased cholesterol, thyroid dysfunction, immune suppression, and some cancers. Children and pregnant women draw special concern. This knowledge shaped my perspective years ago, teaching science students about real-life cases in small American towns where PFAS showed up in tap water.

Pushing for clearer labelling on products containing persistent chemicals would let people choose products more wisely. Strengthening standards for discharge from factories and requiring regular testing at known sites could catch problems before they spread. Governments should empower public health agencies to update the public about what’s found locally—anyone living near an industrial site or airport should get regular updates on water quality.

Successful cleanups demand more than switching out one chemical for another. The United Nations calls for global cooperation, echoing how these substances ignore legal boundaries. Tools like the Stockholm Convention target chemicals proven to stick around and harm health. Including this acid on that list would send a clear message: The world stands ready to phase out the old and keep water safer.

Laws alone don’t solve everything. People living in affected communities need support—replacement water, health monitoring, stronger reporting from manufacturers. Citizens who feel left out of regulatory processes want governments to listen, not dismiss their worries.

PFAS in drinking water holds up a dirty mirror: Technology invented for comfort now brings costly consequences. Open conversations and honest reporting, backed by stricter and more unified laws, help protect everyone down the line.

| Names | |

| Preferred IUPAC name | 2,2,3,3,4,4,5,5,6,6,7,7,7-Tridecafluoroheptane-1-sulfonic acid |

| Other names |

Perfluorooctanesulfonic acid PFOS Heptadecafluorooctanesulfonic acid Perfluorooctylsulfonic acid Tridecafluorooctanesulfonic acid |

| Pronunciation | /ˌtraɪˌdiːˌkæfluˌɔːkˈteɪn.sʌlˌfɒnɪk ˈæsɪd/ |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | 756-16-5 |

| Beilstein Reference | 635915 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:38897 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL3112084 |

| ChemSpider | 160436 |

| DrugBank | DB02951 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 035a3b1b-2a73-438d-ac51-eae68193b32b |

| EC Number | EC 206-203-2 |

| Gmelin Reference | 71405 |

| KEGG | C19591 |

| MeSH | D000077247 |

| PubChem CID | 67640 |

| RTECS number | TT2975000 |

| UNII | R8AX8U3F7R |

| UN number | UN3318 |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | DTXSID40101585 |

| Properties | |

| Chemical formula | C8HF13O3S |

| Molar mass | 538.152 g/mol |

| Appearance | Colorless or light yellow liquid |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | 1.85 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | Soluble |

| log P | 3.12 |

| Vapor pressure | 15.4 Pa (20 °C) |

| Acidity (pKa) | -0.3 |

| Basicity (pKb) | -5.3 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | Diamagnetic |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.328 |

| Viscosity | 180 cP |

| Dipole moment | 5.6 D |

| Thermochemistry | |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 544 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | –1532.7 kJ·mol⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) | -5664.8 kJ/mol |

| Pharmacology | |

| ATC code | C10AX13 |

| Hazards | |

| Main hazards | Causes severe skin burns and eye damage. May cause respiratory irritation. Toxic if swallowed. Toxic to aquatic life with long lasting effects. |

| GHS labelling | GHS05, GHS06, GHS08 |

| Pictograms | GHS06,GHS08 |

| Signal word | Danger |

| Hazard statements | H301, H314, H373, H411 |

| Precautionary statements | P260, P264, P273, P280, P301+P330+P331, P305+P351+P338, P310, P321, P391, P501 |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | 3-3-2-~ |

| Flash point | > 87 °C |

| Autoignition temperature | 310°C |

| Explosive limits | Lower: 1.7% ; Upper: 10.6% |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 Oral Rat: >2000 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | LD50 (median dose): Rat oral 2000 mg/kg |

| NIOSH | GBG300 |

| PEL (Permissible) | PEL (Permissible Exposure Limit) for 3,3,4,4,5,5,6,6,7,7,8,8,8-Tridecafluorooctanesulphonic Acid (PFOS) is not established |

| REL (Recommended) | 0.01 mg/m³ |

| IDLH (Immediate danger) | 30 mg/m3 |

| Related compounds | |

| Related compounds |

Nonafluorobutanesulfonic acid Perfluorooctanesulfonic acid Heptadecafluorooctanesulfonic acid Perfluorobutanesulfonic acid Perfluorodecanesulfonic acid |